Isaac Stanley-Becker

Tuesday February 26, 2019

The oval-shaped brain of a honeybee is roughly the size of a single sesame seed. It contains fewer than 1 million neurons, while the human brain contains 100 billion.

A team of entomologists is asking what all those extra nerve cells are good for after finding that bees can do the kind of vital math once thought to distinguish humans and the primate animals they most closely resemble.

Many animals display some degree of quantitative understanding as they forage and fight, hoard and hide and find their way back home. Counting, for instance, is pervasive.

But bees can do something more, according to a paper published earlier this month in the peer-reviewed Science Advances journal. They can add and subtract, placing one of the world’s leading pollinators in the venerable company of monkeys, parrots and, yes, spiders — the cognitive A-list of the animal kingdom.

The findings contribute to a growing body of evidence that the brains of insects are more powerful than once thought — capable not just of a vague numerical sense but of the sort of learning and complex memory tasks that make arithmetic possible. It also sheds light on the evolution of quantitative abilities in other species, decoupling numerical understanding from human language.

“A small biological processing system can perform quite complex things,” said Scarlett Howard, the paper’s lead author and a postdoctoral fellow at the French National Center for Scientific Research.

The research builds on the discovery of the same researchers last year that bees understand nothing. That is, the concept of nothing. The authors reported that bees trained to perceive notions of “greater than” and “less than” were also able to order zero at the beginning of a numerical continuum — a capacity that put them on the same plane as the African gray parrot, notable for its ability to copy human speech, as well as nonhuman primates and even preschool children.

In the new study, conducted last year at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in southeastern Australia, the researchers devised a Y-shaped maze to train 14 bees to add and subtract.

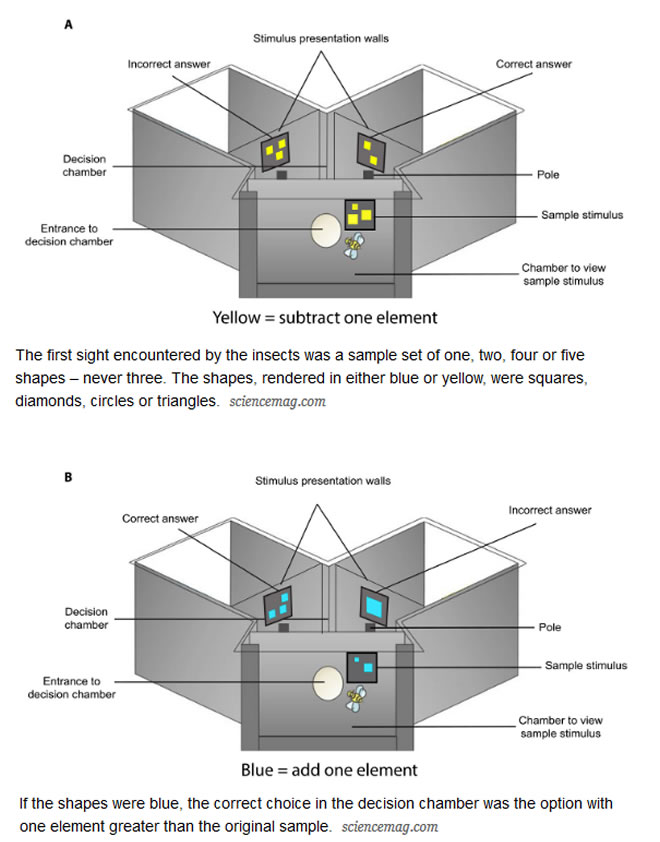

The first sight encountered by the insects was a sample set of one, two, four or five shapes — never three. The shapes, rendered in either blue or yellow, were squares, diamonds, circles or triangles.

Then, they flew into a “decision chamber,” were they came face-to-face with two new sets of shapes.

If the shapes were blue, the correct choice in the decision chamber was the option with one element greater than the original sample. If the shapes were yellow, however, the right move for the bee would be to fly in the direction of the option with one element less than the sample.

They were rewarded with a sugary solution for correct answers and punished with a bitter-tasting substance for misfires.

At first, the insects made random decisions. But across 100 trials each, the bees came to understand when they were supposed to choose the +1 or the -1 option.

The task required two cognitive feats at once: long-term recollection of the color rule and shorter-term analysis of an unfamiliar number of shapes.

Though each bee appeared to learn differently, the population showed signs of mastery somewhere between the 40th and 70th test, Howard said. Over time, they took to slowing down when presented with the initial sample, before racing into the decision chamber.

Then, the bees were put to the test, faced with a shape they had never seen before, as well as a novel number of sample elements: three. Each bee performed four tests, each consisting of 10 trips through the maze. In each test, conducted without punishments or rewards, the bees performed significantly better than chance.

They appeared not to master one command better than the other, though other species have shown signs of favoring addition, Howard said. She added that the results were conclusive enough that the researchers felt confident with their hive of 14 bees. Eight to 12 is considered statistically sound, she said.

The new evidence of the honeybee’s computational skills comes as its numbers dwindle under mounting threats from pests and pathogens. Beekeepers in the United States lost 40 percent of their managed colonies between the spring of 2017 and the spring of 2018, in line with a broader decline of invertebrate populations, which scientists have linked to climate change.

The discovery holds applications beyond the activities of honeybees alone.

“A honeybee brain contains less than 1 million neurons, so evidence that a bee can learn to use a mathematical operator is very important for our understanding of how big brains, like ours, may have plausibly evolved the capacity for the incredible mathematical achievements that underpins our modern society,” said Adrian Dyer, one of the study’s authors and an expert on imaging and information processing at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.

The discovery casts doubt on the idea that numerical understanding is innate to humans, who are separated from honeybees by more than 400 million years of evolution, as the paper notes. The result suggests instead that bees, nonhuman animals and pre-verbal people may each be “biologically tuned for complex numerical tasks,” a capacity honed through the struggle for survival in “complex environments that have forced them to use numbers and quantify,” Howard said.

“We’re not the only sophisticated ones,” she said.