FoodTank

Monday May 14, 2018

By Amialya Durairaj

Americans settlers have a long history bringing their favorite foods with them when they emigrate. Wheat, cattle, and pork, for example, were all imported into the United States from Europe. Now, a small group of Somali Americans are continuing that tradition by introducing camel meat to the American Midwest.

In spite of the recent restrictions on immigration, the Somali population has grown in the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, the Somali community in America increased from 2,500 in 1990 to almost 150,000 in 2015[DN1] . Roughly 30 percent of these Somali Americans call Minnesota their new home, making it the U.S. state with the largest Somali population.

In the vibrant Little Mogadishu neighborhood of Minneapolis, restaurants and grocers try to cater to their East African customers’ desires. And, for many Somalis, a taste of home means eating camel.

Camel is an economically and nutritionally important livestock animal for pastoral Somalis who live in a harsh and arid climate. In addition to providing a source of meat and dairy, the animals are employed as vehicles, laborers, and even as a type of currency. The meat has particular cultural resonance, as animals are frequently eaten at weddings and other special occasions.

But, as with many other types of imported foods, the form that camel meat has taken on plates has morphed over time. While traditional camel dishes may satisfy some, other diners are interested in Somali-American fusion.

For these customers, Safari Express, located in the Midtown Market of Minneapolis, offers camel burgers. In their recipe, ground camel is marinated with East African spices and served on a bun with pineapple, lettuce, tomato, red onion, cheese, and chipotle mayo. The novelty and taste of this burger, specifically, have attracted press to the restaurant and its co-owners Jamal and Sade Hashi.

Of course, camel herds are not known to roam the Great Lakes region. So where is the meat coming from? The answer, it turns out, is Australia.

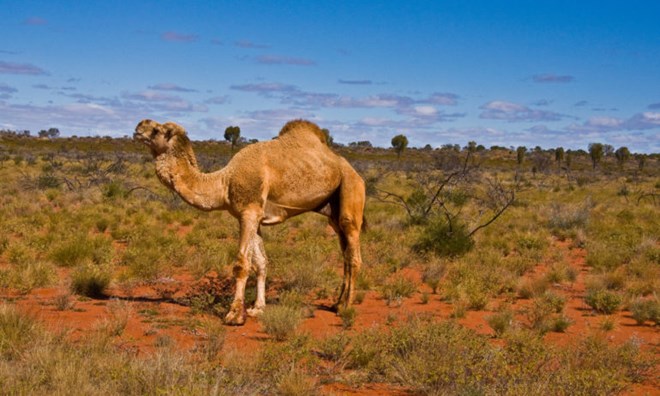

While camels are not native to the country, they’ve found a hospitable climate in the outback. In the 19th century, settlers imported camels from the Middle East and Asia to use for labor and transportation.

When the camels were no longer needed, they were set free. This led to Australia becoming home to the world’s largest feral camel herd. In 2013, a report by Ninti One Limited and the Australian government estimated that there were about 300,000 feral, one-humped dromedaries in the outback.

Some claim these feral animals have caused environmental and infrastructure concerns. In 2009, the Australian government awarded a grant worth US$14.7 million dollars to Ninti One Limited to help solve the perceived pest problem. Their Australian Feral Camel Management Project culled large portions of the herds.

Other experts are skeptical of the idea that the invasive species are causing harm. Some scientists, like Dr. Arian Wallach of the University of Technology, Sydney, have argued that feral camels are helping the Outback environment. By reintroducing grazing, the herds may reduce the dangers forest fires while fertilizing the soil with their dung.

And to some entrepreneurs, Australian camels represent an untapped opportunity.

Paddy McHugh, a Queensland-based entrepreneur in the growing camel industry, catches camels and handles the logistics of export across the world. McHugh has found that the demand for the animal—whether for it is meat, milk, entertainment, or labor value—continues to grow. “We get inquiries all over the world. We’ve had 1,000 different inquiries from 70 different countries,” he says. “We struggle to supply that.”

According to McHugh, because of the country’s current regulations, camels are rarely slaughtered in Australia. Often, the animals are exported to Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Egypt, Malaysia, or the United Arab Emirates to be killed by halal methods. Because camel meat is popular with Muslim customers, halal certification is crucial for marketability.

Once the camels have been slaughtered, their meat is sold in markets to specialty meat distributors. These companies import into the U.S. to sell to smaller vendors, grocers, and restaurants.

Based in Reno, Nevada, Sierra Meat & Seafood Co is one such company. In addition to more standard fare, they supply American businesses with exotic meats.

Rich Jersey, Senior Vice President of Specialty Meat and Game, says that “we buy from packing houses in Australia which is a big export market.” The halal-certified meat is then imported into the U.S. where Sierra Meat & Seafood Co sells it to their customers.

While the company offers a variety of options, finely ground meat is their most popular camel product. Often, Jersey says that boutique burger outlets purchase it when they want to add new specialties to their menu. Nutritionally, camel’s lean meat is high in protein and low in both saturated fat and cholesterol.

McHugh, who has eaten camel hundreds of times, says that the method of slaughter can make the difference between a delicious or terrible bite. Jersey describes camel meat as “similar in taste to high-quality venison or grass-fed beef.” Others have described it as akin to bison.

In the U.S., camel is still considered a novelty meat, according to Jersey, and it is priced similarly to beef. However, the increased demand in America, Japan, and Europe led to a 20 percent increase in production for the Queensland camel-rearing company Meramist in 2012. In 2016, the owner of the California-based Exotic Meat Market reported a 3,000 percent increase in camel meat sales to The Washington Post, though official U.S. sales numbers have not been tracked.

Compared to other large livestock, feral camels require less vegetation and water. The meat’s nutritional qualities, coupled with these low production inputs, may make it a more sustainable animal-based protein source. “They are a great animal to domesticate,” McHugh says. “We should be farming and harvesting camel for the food security of the world.”

The growth of the Australian camel industry could also employ more Aboriginal people living in remote Australian communities, according to Meat & Livestock Australia Limited.

But the environmental impacts of shipping camel halfway across the world have not yet been explored, as well as the costs and risks of establishing a camel trade. Whether the U.S. demand for camel meat will grow in the coming years is unclear. But, for now, Somali-Americans can experience a taste of home in Little Mogadishu.