by Mohamed I. Trunji

Monday, March 18, 2019

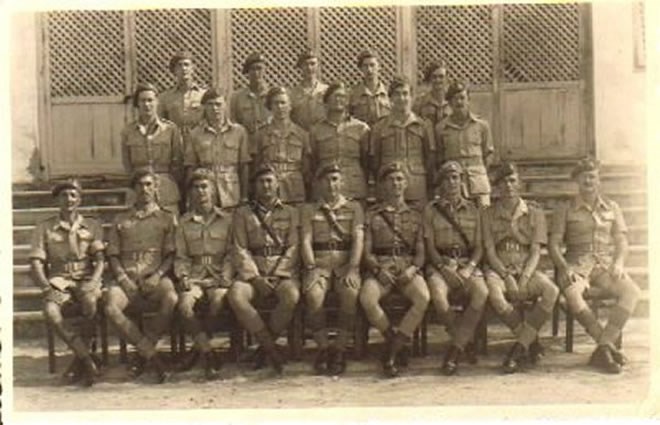

British troops in Mogadishu after defeating Italian troops in Somalia - 1941

The year 1941, Seventy-eight years ago, was a historical one in the history of Somalia; it marks the date it came under unexpected British military occupation, putting an end to fifty years of Italian domination. Somalia had been under British military rule between 1941 and 1949. This article looks into the economic difficulties and the injustice the Somalis endured under the British military rule. It takes due account also of the climate of political liberalization inaugurated by the British.

Background: Following Italy’s defeat in the Second WW, the Italian Somaliland, the Protectorate of Somaliland and province of Ogadenia were placed under the Command of East Africa, based in Nairobi, Kenya. Initially, the administration of the territory was known as “Occupied Enemy Territory Administration” (OETA) The administration’s name was changed in 1942, with the removal of any reference to “enmity” to become “Occupied Territory Administration” (OTA) The name of the administration was again changed to “British Military Administration” (BMA) and, lastly, on the eve of placing Somalia under international trusteeship regime, to “|British Administration of Somalia”. (BAS)

The main concern of the British colonial authorities, throughout its nearly 10 years tenure, was to maintain under strict control the security situation of the territory, acting quickly to confiscate the weapons in the hands of some irregular elements, ex Italian servicemen who were using the weapons to raid local populations. To this end, a Gendarmerie Force was established after the Italian police in Mogadiscio had been disbanded on 16 April 1941 (Rennel, 1948) The top priority accorded to the security question is evidenced by the sheer size of this force.

In fact, by the end of 1943, the Somali gendarmerie force consisted of 3,070 Somali and African ranks, 120 British officers, some 200 riding and pack camels, 250 horses and mules and a squadron of armoured lorries ( Rennel, 1948) Hundreds of British trained gendarmes were unleashed to capture herds of animals found on their way, irrespective of whether the owners were in possession of illegal weapons arms or were unarmed peaceful herdsmen with no association with the disbanded Italian troops. The collective punishment included acts such as picketing of the wells where the animals would be brought for watering, thus increasing the chances of seizure of large amount of animals.

Once the camels were taken, they remained in the hands of British forces and were kept in a thorn stockade and only released if and after any weapons were handed in. It is scarcely surprising that a number of camels should die from disease and lack of care in captivity, under the eyes of the impotent herdsmen. The practice of keeping the raided camels in a stockade near a water hole was dubbed as ‘geel ood’, meaning ‘camel enclosure’ (Barnes, Cedric, 2007) It is also reported that, during one of these blanket disarmament campaigns, from December 1944 to April 1945, an estimated 26,000 camels were seized in Ogaden alone.

The British military administration in Somalia was not so much concerned with international law or wider issues as with efforts to reinstate internal law and order. The harsh methods used by the colonial authority prompted Abdulkadir Sakawaddiin, the Somali Youth Club leader, to address in 1946 an open letter to the British Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Attlee, in which he vigorously protested against the methods used by the British, especially the collective punishment, reminiscent, as he put it, of the Fascist regime.

Somalia under Two flags (Somalia sotto Due Bandiere)

I have borrowed this title from Antonia Bullotta’s famous book “Somalia Sotto Due Bandiere”, published in 1949.

British propaganda of the time presented the British troops in Somalia as liberation force freeing the territory from Fascist occupation. However, after the euphoria of the first few months, the Somalis had to come to terms with a different reality. In fact, the first proclamation issued by the chief military administrator, Gen. Alan Cunningham, reads: “The powers to be exercised under my authority by the military authorities are intended to supplant and not to supersede the civilian Administration, meaning the pre-existing Italian Civil Administration, and law courts, municipalities, councils and civil officials are hereby requested to continue the punctual discharge of their respective duties until otherwise ordered.” (WO230/4, Proclamation n. 1, 1941) Scores of Italian civil officials, who had served under the defunct Fascist regime in Somalia, were thus hired through a careful selection process.

Only those individuals deemed not to be a security risk were included in the system, while those seen as suspicious were either interned or repatriated to Italy. British source reveals that “The Italian laws have, in general, been respected and great care has been taken to preserve the fiscal structure to the fullest extent possible. The Mogadiscio Municipality has functioned throughout as an Italian department under a ‘Commissario Straordinario’ appointed under Italian law.” (FO1015/149 report dated November 25, 1946)

Owing to scarcity of experienced personnel and financial resources, the British military officials had to rely upon the services of many experienced Italian civil servants. “A ridiculously small band of civil affairs officials, many of whom had no previous colonial experience arrived in Somalia to deal with the chaos left behind by the fighting”, comments Lewis (Lewis, 2002)

Ordinary Somalis did not feel there was much difference between the Italians and the British who replaced them, despite the latters portraying themselves in wartime propaganda as ‘liberators’. Both the Italians and the British were seen by the local people simply as Gaalo, a Somali term for people of European descent.

The Somalis were mindful of the injustice done by the Italians especially in imposing forced labour to the benefit of the Italian settlers engaged in agriculture; but neither has there ever been excessive sympathy, between the British and the Somali public at large, as one British writer seemed to argue. Bitter memories of the brutal methods used by the Gendarmerie under British command and the havoc they had created in looting and raiding nomad’s herds still lingered in the minds of many Somalis who had suffered as a consequence.

The racial laws remained in place. “In Mogadiscio, bars and restaurants reserved only for Europeans are not serving natives”, comments Antonia Bullotta. This situation was an element of confusion in the Somali mind.

Somalia plunges into economic hardship

From the economic point of view, the territory was plunged into such economic hardship as had never been experienced in pre-war time. As we have mentioned earlier, in the years immediately after the war, coinciding with British military occupation, much attention was given to the maintenance of security in the territory, leaving other aspects of the population’s life unattended.

In particular, the British gave little attention to promoting the great economic potential of southern Somalia, preferring instead to wait and see how events would evolve with regard to the future status of the African territories captured from Italy.

Agriculture, long touted to the Somalis as the cornerstone activity that would guarantee food security, was not developed to any real extent. Predictably, this brought misery and deprivation to the local communities. Gone were the days of abundance of food and modest welfare guaranteed through employment under the Fascist regime.

A report of the United Nations in 1950 found that three-quarters of the cultivated land were abandoned, farms have lost much of their mechanized agricultural tools, and the irrigation system had become useless through lack of maintenance.

At the outbreak of the war, there was substantial number of enterprises, consisting mostly of transport and building firms, as well as light manufacturing industry based on local produce.

The Italians introduced public utilities and amenities to the towns, built roads, introduced medical and veterinary services and examples of modern farming methods. They also developed some modest public services such as water, health, and schools.

“The British Administration, in view of the temporary nature of its occupation and in accordance with the regulations governing occupied territories contained in The Hague Convention of 1907, followed a ‘care and maintenance’ policy, initiating no long term programmes and limiting themselves to dealing with immediate requirements and problems, mainly connected with security”. (Four Power Commission of Investigation for former Italian Colonies, 1948)

Furthermore, the British Administration had demolished or transferred a number of existing small industrial plants or vital infrastructure. The industrial plants and machineries of all sorts demolished or transferred for military use in other theatres of war included:

(a) Electric generating plant in Mogadiscio

(b) Elaborate salt works at Dante (Hafun) The salt deposits plant were producing more than 200,000, tons annually, most of which was exported to the Far East (Hess, 1966)

(c) Majayahan and Kandala (Migiurtinia) mining quarries (Four Power Commission of Investigation for former Italian Colonies, 1948)

(d) 70 miles of narrow-gauge railway track linking Mogadiscio, Afgoi and Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi (Jowhar)

(e) The Afgoi Bridge on the Uebi Scebeli River

(f) The oil storage plant and the oil seed crushing plant in Mogadiscio

The economic structure built by the Italians before the war was gradually destined to collapse, with disastrous consequences.

The deteriorated economic situation hit equally Somalis and Italian community in Somalia. Many workers lost their jobs, and most of them remained unemployed throughout the British military occupation. The Protectorate of Somaliland was in a worse economic situation than Somalia under occupation.

In contrast with the Italian colony, British Somaliland remained a neglected backwater. Britain used its colony as little more than a supplier of meat products to its military garrison in Aden. Establishing a comparison between the degree of development achieved in the territories inhabited by Somalis, I.M.

Lewis writes:”…Whatever their motives, and notwithstanding the impress of Fascism, decidedly more of benefit to Somalis had been created in Somalia than in British Somaliland, French Somaliland, or, above all, in the rotten province of Kenya which for long was destined to remain a stagnant back-water. (Lewis. 2002) The dramatic economic situation in the former Italian colony during the British Military occupation was further confirmed by official colonial sources in the sense that “Life was perhaps easier and the means of living more plentiful than they are today” (FO 1015/149) Severe shortages prompted rationing of food and other basic necessities throughout Somalia in some years during British military administration: “People had to queue up for long hours inside barbed wire corridors created in the middle of the Souk”, (Sharif Salah Mohamed Ali ) For the majority of the Somalis, already disoriented by the destruction caused by a war not of their making, the British, with their strong military presence in Somalia (Kikuyu, Tanganyikans, Ugandans, Nyassalanders, etc. etc) were viewed as new colonial rulers.

The Somalis are mindful of how repeatedly Britain had frustrated their national aspirations for unification when she returned the Ogaden to Ethiopia in 1948, and resorted the Haud pastoral land, adjacent to British Somaliland, to Ethiopia in 1955, before unilaterally tracing a new frontier, the so-called ‘provisional administrative line’, with Ethiopia, shortly before Italy took over the administration of the Trust Territory under UN Trusteeship in 1950.

Yet, to do the British justice, Somalis received encouragement to first set up cultural clubs, and then to organize themselves into political organizations, a fact Aden Abdulla, future President of the Somali Republic, eloquently used to embarrass Giuseppe Brusasca, Italian Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs, who arrived Mogadiscio in May 1950, the first high profile visit to Somalia by an Italian official since the end of the war.

During his mission in Somalia, Brusasca met some exponents of the Lega dei Giovani Somali, led by Aden Abdulla, who was then serving as Secretary of the party’s branch in Belet Uen.

When Brusasca started pointing out, during the conversations, the improvements achieved by Italy during its tenure as colonial power, Aden Abdulla, in a very matter of-fact manner, responded to his interlocutor “But those who came after you (the British) granted us some thing immensely much more important than that. They gave us freedom of expression, freedom to establish political parties, freedom to work for the future of our country: rights the Italians denied to the people.” (Del Boca, 2002)

On April, 1950, as provided by the General Assembly of the United Nations Resolution, the transfer of administration from the British to the italians was formalized with solemn ceremony. The handover process took place in all over the territory.

In Mogadiscio, the ceremony of lowering and hoisting flags took place in the courtyars of the Governnment Palace, widely known as “Palazzo del Governo”. By an irony of fate, the last Italian flag in the Horn of Africa having been lowered in Gondar, in north-western Ehtiopia, on November 1941, that flag was again hoisted in East Africa, on April, 1950.

Mohamed I. Trunji