Friday February 3, 2023

By Ayaan Mohamud

When I wrote my first young person’s novel, I wanted the next generation to feel seen and celebrated

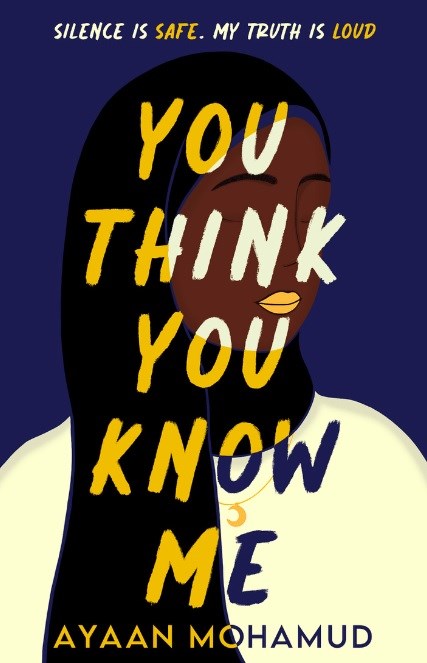

‘With hindsight, I wonder why I never stumbled across books with a diverse cast of characters, and feel saddened that I never stopped to question their absence.’ Photograph: Ayaan Mohamud

As a teenager in the British Somali diaspora, there were several things I heard repeated in connection with my own culture. In no particular order, there was: drought, Black Hawk Down, high foreheads, piracy, famine, the peculiarity of banana and rice, terrorism, and the “look at me, I am the Captain now” meme. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t always feel “cool” to be Somali.

When this feeling was coupled with the age-old question of who Somalis are, I found it hard to carve out my own sense of identity. Torn between the country’s physical location on the Horn of Africa, our ethnic homogeneity, and Somalia’s membership of the League of Arab States, it often felt as if I was being pulled in a million different directions. Was I Black, east African, Arab or simply … Somali? And how did my identity as a Muslim fit on to these racialised lines?

None of this was helped by the lack of authentic representation of Somalis in literature. As a child, I was a voracious reader. I devoured books by authors like Meg Cabot, Anthony Horowitz, and Jenny Nimmo. As I got a little older, I set my sights on Jane Austen, Cassandra Clare and John Green. With hindsight, I wonder why I never stumbled across books with a diverse cast of characters, and feel saddened that I never even stopped to question their absence.

My first memory of reading a book featuring a Black character was Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses. Years later, when I started my English literature AS-level course, the floodgates that I hadn’t known existed finally opened. I read Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. I read Mohsin Hamid. I read it all and loved it.

Throughout those years and the ones that followed, I became acutely aware of what I read – of the words and the characters on the page – and the occasional feelings of dissociation in doing so. I have loved seeing fragments of myself reflected in print, through the various takes on the Black British experience or the experience of being Muslim told through the lens of a South Asian or Middle Eastern character. But it wasn’t until three or four years ago that I realised the experience still felt incomplete.

"Teens need to see themselves reflected on a page to counteract the negative perceptions that hound the Somali community"

This became clear when I discovered and read Black Mamba Boy, by Booker prize-shortlisted author Nadifa Mohamed; clarified when I came across Warsan Shire’s brilliantly haunting poetry in her debut pamphlet,

Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth. Here, finally, were the British-Somali voices I didn’t know existed. Here were the stories that I didn’t know I needed. I found my people in the heart-wrenching words of Shire’s

Conversations About Home, giving voice to the anguish of Somali refugees, and in Mohamed’s exploration of a colonised 20th-century Somalia, told through the lens of a boy trying to find himself in an unforgiving world. The comfort these tales gave me, the joy in feeling seen – of being visible – was one of the greatest gifts I have ever received. And, in those moments, I felt that the void must have well and truly been filled with the magic I had found. What else could I possibly want or need?

A stunning debut about finding the strength to speak up against hate and fear, for fans of The Hate U Give and I Am Thunder.

A stunning debut about finding the strength to speak up against hate and fear, for fans of The Hate U Give and I Am Thunder.

The tragic story of

Shukri Abdi stopped me in my tracks. Her death stayed with me, and for much of the UK Somali community, for a long time. The devastating circumstances of her death and the police handling of the incident left me dazed, contemplating her story time and time again. What must it have been like for a young Somali refugee to come to this country? To face ridicule for being different, while struggling to integrate into a society so foreign from the one they had known?

My debut Young Adult book, You Think You Know Me, was born of those thoughts, and I realised what had been missing was voices for children. Accessible narratives of drama, adventure, heartache, legend, joy, drama, myth, featuring Somali characters.

Teens and younger readers need to see themselves reflected on a page to counteract the negative perceptions that hound the Somali community. How else will they be able to clearly see themselves within their kaleidoscopic identity? My story has a cast of unapologetic Somali characters who value every aspect of who they are. They are refugees, Muslim, Black, and they are proud of it. They speak English, Somali and Arabic. They eat the food of their homeland and wear their traditional clothes. They use the proverbs of their people to guide themselves and each other. They have left home but they carry home with them, in everything that they do.

I am proud of

You Think You Know Me adding to the growing discourse around cultural representation, and there are others paving the way too.

Somali Sideways, an international platform dedicated to subverting negative perceptions through photographing and documenting the lives of Somalis, is doing exceptional work to this end. The annual Somali Week festival has also made huge progress in dismantling the dangerous “single story” of Somalis.

Here is what I am hoping the next generation of Somali children will hear and internalise: that we are many things, that we come from a beautiful but struggling homeland, that we are descendants of poets and nomads – but most importantly, that we can be anything we want to be.

Ayaan Mohamud is a British Somali author and medical student