Friday September 16, 2022

Analysis by Mike Cohen

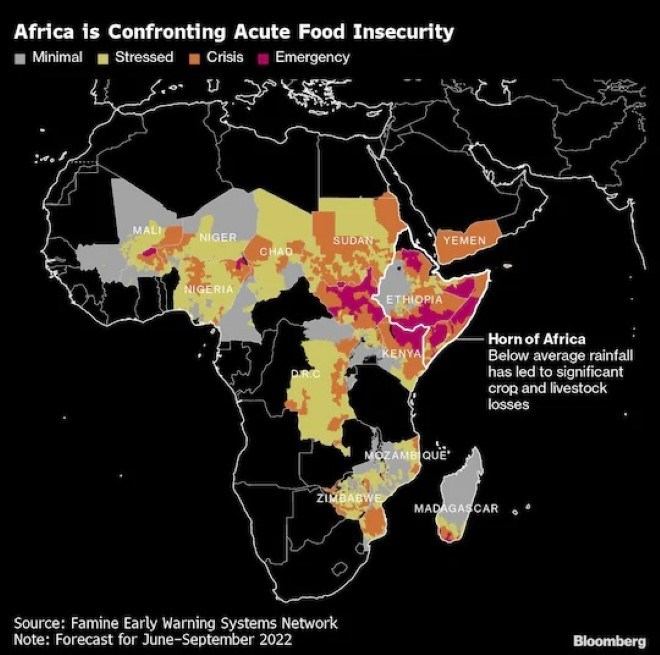

Why East Africa’s Facing Its Worst FaminA humanitarian disaster is unfolding in the Horn of Africa, which is in the grip of its worst drought in at least four decades. More than 20 million people in Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya are struggling to find enough to eat, and over 1 million have fled their homes, according to the United Nations. With forecasters seeing a high risk of rains failing for a fifth consecutive season and aid flows falling short of what’s needed, the region is at risk of a famine that’s on a par with -- or even worse than -- one that Ethiopia experienced in the 1980s and claimed an estimated 1 million lives.

1. How dire is the situation?

Malnourishment is already widespread, especially among children, millions of whom need treatment. Millions of head of livestock have died, vast swathes of cropland have been decimated and rural communities have been torn apart as families migrate in search of food and grazing. Many parents can’t afford to keep their children in school, drop-out rates have soared and there are reports of girls as young as nine being married off for dowry payments or to ease economic pressure on households. The UN’s emergency relief coordinator, Martin Griffiths, said he’d seen starving babies who were too weak to cry when he visited Somalia in September. The UN expects a famine to be formally declared in parts of Somalia in the last quarter of 2022. The classification is assigned to areas where at least a fifth of households face an extreme lack of food, at least 30% of children suffer from acute malnutrition and at least two out of every 10,000 people die daily from starvation or a combination of hunger and disease.

2. What’s the backdrop?

Climate change has resulted in extreme weather patterns, and nations across Africa have increasingly been contending with drought and flash floods. The coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have compounded the continent’s woes, making it more expensive and difficult to obtain supplies of food, fuel and fertilizer. Food prices have since eased, but relief has yet to filter through to most consumers. While Europe, parts of the US and other regions are also experiencing severe droughts, they are better equipped to deal with the fallout than cash-strapped African nations.

3. Are there other contributing factors?

Locusts, which thrive in hot and dry conditions, have wiped out crops across large parts of eastern Africa. Somalia and Ethiopia have also been contending with internal conflict that’s disrupted farming and made it dangerous to distribute aid. In Somalia, militant group al-Shabaab has been trying to topple the government since 2006 and impose its version of Islamic law. And in Ethiopia, the government and rebels from the northern Tigray region fought a civil war that dragged on for more than 16 months before a truce was agreed in March. Fighting flared again in September, raising fears of a return to all-out war. Kenya held presidential elections in August that may have diverted some attention away from the drought.

4. Who has been trying to help?

The US says it gave more than $6.6 billion in humanitarian and food assistance to Africa in the first seven months of 2022, which would make it the single biggest donor. The European Union, Canada, Sweden, Germany and the UK were also leading contributors. Kenya’s government has introduced corn and fuel subsidies but says it can’t afford to maintain them indefinitely. While Somalia needs $1.5 billion to help 7 million needy people -- almost half the population -- only 70% of that had been pledged by mid-September, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The shortfall was even bigger for Ethiopia, with just 40% of the $3.1 billion that’s required to help 20 million people committed.

5. What about the rest of the continent?

Several other sub-Saharan countries are confronting hunger crises of their own, among them South Sudan, Sudan, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali. The International Monetary Fund estimated in September that at least 123 million people across the region, or 12% of the population, won’t be able to meet their minimum food consumption needs, an increase of 28 million over just two years. Contributing factors included soaring food prices, depressed incomes, extreme weather events, insecurity and disruption of supply chains.