Tuesday May 31, 2022

By Aodhan O'Faolain

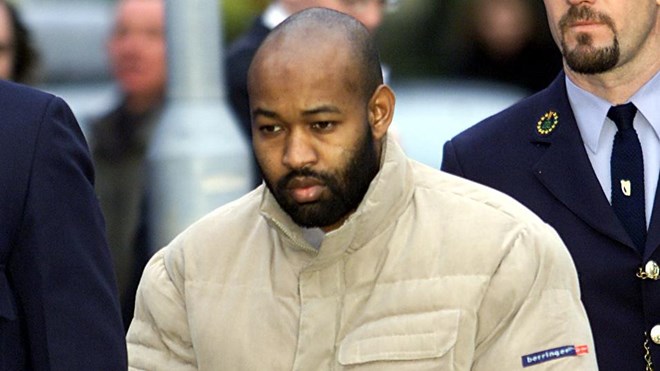

Yusuf Ali Abdi, whose last address was The Elms, College Road in Clane, Co Kildare, stood trial in 2003 for the murder of Nathan Baraka Andrew Ali, at that address in April 2001.

The Supreme Court has upheld a finding that a mentally ill man’s wrongful conviction for the murder of his infant son amounted to a miscarriage of justice.

The five-judge court made its ruling when dismissing an appeal brought by the DPP in a case concerning Yusuf Ali Abdi.

Mr Abdi is a Somali native who served 16 years in an Irish prison before his 2003 conviction for the April 2001 murder of his 20-month-old son, Nathan Baraka Andrew Ali, was overturned at a retrial in late 2019.

The jury at his retrial found him not guilty by reason of insanity after psychiatrists for the prosecution and defence said that at the time of the killing, Mr Abdi with an address at Charleville Road, Phibsboro, Dublin, was suffering from delusions arising from schizophrenia.

The Central Criminal Court, and subsequently the Court of Appeal, both agreed that the 2003 conviction amounted to a miscarriage of justice.

Arising out of those decisions he was granted a certificate under the 1993 Criminal Procedure Act allowing him to seek compensation from the State.

The DPP appealed that finding to the Supreme Court.

On Monday, the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal and agreed that the certificate should have been granted in favour of Mr Abdi.

Giving the court's decision, which clarifies the issues concerning 'miscarriages of justice' applications, Mr Justice Peter Charleton said he considered the origins of the defence of insanity through to the modern version of the defence, as defined in the 2006 Criminal Law (Insanity) Act, and noted that the burden of proof of the commission of the facts constituting the offence remains on the prosecution.

The consequence of a finding of insanity, he said, is "a lack of coincidence between the external and mental element of an offence, thereby rendering the act no longer criminally culpable".

These circumstances arise where an individual does not know the nature and quality of the action by virtue of their mental state, and therefore does not commit an offence, he said.

In relation to the burden of proof in relation to the defence of insanity, the judge said in cases involving diminished responsibility, and those relying on the defence of insanity, the accused must demonstrate clearly that their mental state was removed from the mental element of the offence.

Where this is proven, he said, "no liability can arise in the accused, as the absence of capacity negates the fundamental definitional element of the crime".

He added that it is "plainly incorrect to suggest that an individual, by virtue of their having carried out an action upon which a criminal charge was brought, remains somehow guilty despite acquittal".

He said that "an acquittal generally is not a finding of innocence", but rather "a statement that the presumption of innocence has not been displaced beyond reasonable doubt".

The judge also held that fault on the part of the prosecution is not a requirement under the 1993 Act.

He said that a miscarriage of justice must be established by the accused, as an applicant for a certificate, and that such a case is shown where there is a “substantial failure of the system to administer justice”.

Where innocence is not demonstrated in consequence of an acquittal on foot of a newly-discovered fact, the judge held that the accused must demonstrate bad faith on the part of State authorities which undermines the justice system or a failure in the administration of justice due to error to such an extent that the prosecution is fundamentally undermined.

Applying this definition of a miscarriage of justice to the appeal in question, the judge said that, as criminal liability is founded on the combination of an external element coupled with a mental element, a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity constitutes a fundamental negation of criminal responsibility.

The verdict delivered by the jury on retrial constitutes an acquittal and, based on Mr Abdi’s lack of guilty mind at the time of the death of his son, the verdict demonstrates innocence, which the judge said applies solely in the context of insanity, and not in the context of the defence of diminished responsibility or any other defence.

In all the circumstances the Supreme Court was satisfied to uphold the Central Criminal Court and Court of Appeal decisions and dismiss the appeal.