Wednesday October 27, 2021

BY KEVIN WAITE

Slaveholders wanted to expand slavery westward. But first they needed to dominate the southwestern deserts.

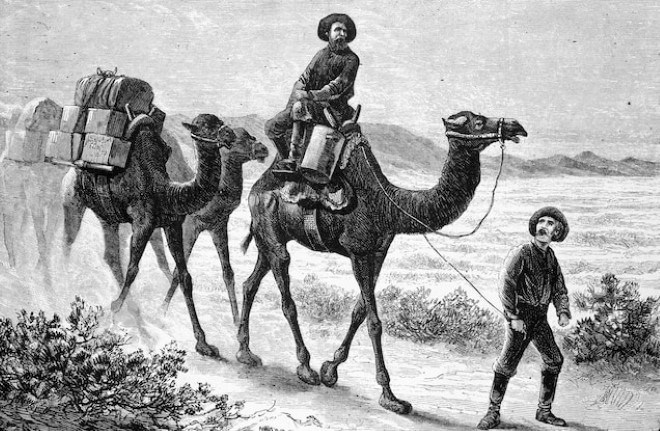

Newly imported camels carry soldiers and supplies in this 1857 expedition of the U.S. Army Camel Corps. Slaveholders hoped that the desert animals would facilitate the westward expansion of slavery. VIA MPI/GETTY

In the spring of 1851, Jefferson Davis, a U.S. senator and the future president of the Confederacy, proposed to import 50 African and Asian camels—“the ship of the desert,” he called them—into the American Southwest. He wanted federal funding to support his globetrotting project; he got only derision.

For Davis, however, camels were no laughing matter. And as whimsical as his pet project may appear today, camels in fact belong to a dark chapter in American history when they were used as instruments of colonial conquest and slaveholding expansion.

Rebuffed in 1851, Davis continued advocating for his camel project. He argued that the animals would become a staple in military operations in the American Southwest, used by soldiers to hunt down Indigenous people in the region, thus asserting U.S. control across the continent. Once safe passage could be secured from Texas to Southern California, he expected white Southerners to begin moving west in large numbers, bringing their slaves with them. Although he denied it, camels were part of his broader fantasies for the westward extension of slavery.

After four years of lobbying, Davis finally won funding for his camel operation in 1855—at which point he was Secretary of War and could oversee the project. His handpicked agent soon set off on a world tour, with stops in Tunis, Constantinople, Cairo, and Smyrna, collecting a variety of “camels and dromedaries,” as well as Turkish and Arab handlers, as he went. A cargo of 34 animals landed in Indianola, Texas, in April 1856. Nine months later, an additional 41 camels arrived in the United States. (Discover why camels are disappearing in India.)

The U.S. military soon set them to work, often drawing crowds of wide-eyed spectators. One camel successfully hauled 1,200 pounds of hay, delighting those who gathered to observe the feat. Between 1857 and 1859, Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale employed dozens of camels in several high-profile expeditions across the Southwest.

The list of American camel enthusiasts was growing. The animals, as observers noted, offered several advantages in desert travel: They could survive without water for long stretches of time, manage heavy loads, travel more than 30 miles a day, and do so while consuming less food than horses and mules. (See the close relationship between Somali herders and their camels.)

Nevertheless, camels never became a fixture in the U.S. military, as Davis had hoped. Critics pointed to a litany of unpleasant personal habits: sneezing, shedding, acute halitosis, general bad odor, and a tendency to regurgitate on passersby. Perhaps even more damaging, rumors circulated that the camel corps was part of Davis’s thinly veiled proslavery plot. Congress refused to appropriate funds for the animals in 1858, 1859, and again in 1860. At that point, more than 80 camels were scattered across forts in Texas and California.

And yet, the story of American camels, and their curious connection to slavery, doesn’t end here. What started as a military project soon caught the eye of deep-pocketed civilians. Once again, slaveholders led the way.

By the late 1850s, camels had created a minor frenzy among planters in the South. None other than Davis’s camel importer, Henry Wayne, sparked the fad by writing a widely republished letter, enumerating the merits of camels in plantation labor. They could be used in lieu of mules for a number of tasks, Wayne argued, such as the transport of large quantities of baled cotton.

Slaveholders began clamoring for camels. “I want one of the ‘critters,’” wrote a correspondent to the Southern Cultivator, “and must beg you to tell me how I can get one, transported or shipped to Macon, Geo[rgia].” In 1858, a cargo of 89 camels docked in Galveston, Texas. Several months later, a further 21 camels arrived in Mobile, Alabama.

Camels take part in an event celebrating the U.S. Army Camel Corps at Fort Davis, Texas, now a national historical site. PHOTOGRAPH BY LUC NOVOVITCH, ALAMY

The relationship between camels and slaveholders runs even deeper. As historian Michael Woods has convincingly argued, camels were likely used as a smokescreen to help smuggle African captives to North America.

The United States had outlawed the African slave trade—though obviously not slavery itself—in 1808. So, transatlantic slave traders devised various ruses to avoid detection. One of those dodges involved transporting camels in the same cargo in which captive Africans were secretly stored in a slave ship’s hold. It’s no coincidence that John A. Machado, the main importer of camels to the United States, was also a notorious slave trader.

Camels provided Machado with a cover. Slave ships were generally detectable by a few signs: large water tanks, substantial food supplies, and the stench caused by the unsanitary conditions in which the captives were kept. Yet any ship carrying a large number of camels also required an abundance of supplies and gave off similarly strong smells. With camels aboard, Machado could explain away these tell-tale signs, so often associated with slavers.

Machado had an additional decoy in his beguiling business partner, Mary Jane Watson, who acted as promoter and saleswoman once the camel cargos were unloaded. The press tracked Watson across the South, never suspecting—or at least never reporting on—Machado’s illicit payload.

The Civil War brought an end to the Machado-Watson partnership, and to this particular chapter in American camel history. Machado enlisted his ship in the Confederate war effort—until it ran aground while attempting to break the Union blockade of Charleston in October 1861. The next year, Mary Jane Watson drank herself to death in Spain. The fate of the enslaved people who arrived with Machado’s camels is unknown.

Although camels made cameo appearances in Union and Confederate armies during the war, they weren’t widely employed. They made better mascots than military mounts. By the end of the war, most had been auctioned off or simply set loose. Some found their way into zoos and circuses—five went to the Ringling Brothers—while others disappeared into the wild. For decades to come, startled travelers reported sightings of strange beasts moving across the desert landscape of the Southwest.

A camel marks Hadji Ali's grave in Quartzsite, Arizona. The Syrian camel handler came to the U.S. in 1856 as part of the U.S. Army’s camel experiment. Ali, who died in 1902, was known as Hi Jolly because Americans couldn't pronounce his name.

PHOTOGRAPH BY LAITH MAJALI

Such sightings contributed to a subculture of American camel lore, including the story of the “Red Ghost,” who purportedly rampaged across the West with a headless rider on his back. Hollywood took some of these stories to the silver screen with Southwestern Passage (1954) and Hawmps! (1976). Inland, a bestselling novel about this historic interlude, ended up on Barack Obama’s summer reading list. A memorial to camel handler Hadji Ali—or Hi Jolly, as his name was mispronounced—still stands in Quartzsite, Arizona. The historic mining town of Virginia City, Nevada, holds camel races every year.

Yet Western apocrypha, however amusing, obscures the most important element of this peculiar history. Transplanted camels were more than mere curiosities. They were tools in a conspiracy to entrench and expand the institution of slavery, beginning with the Secretary of War and continuing with individual planters and slave traders. The senators who snickered at Jefferson Davis in 1851 when he unveiled his pet project had little notion of how deep the plot would run.