By Max Bearak and Naba Mohieddin

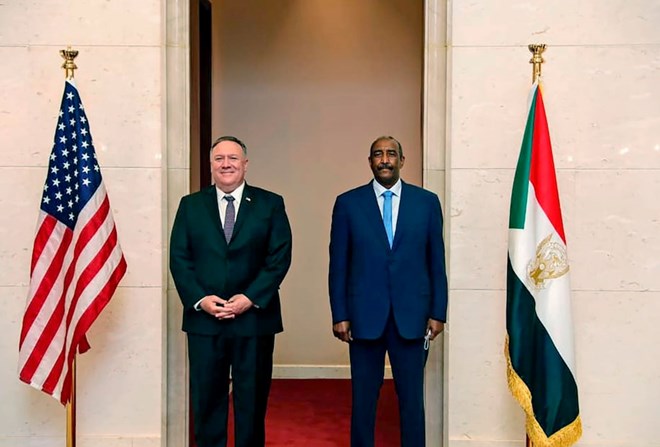

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo with Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of Sudan’s military council, in Khartoum on Aug. 25. (Sudanese cabinet/AP)

Last week, U.S. officials held talks with Sudan in the hopes of adding it to a growing list of countries that have normalized relations with Israel, in what the Trump administration has billed as part of its Middle East peace process.

But negotiations with Sudan have stalled, putting on hold the pre-election momentum of the administration’s earlier diplomatic successes.

Sudan had been working for more than a year toward getting removed from the United States’ list of state sponsors of terrorism, which has blocked the country’s access to the international banking system for nearly three decades. At last week’s talks in Abu Dhabi, U.S. officials presented normalization of ties with Israel as part of a new route to getting off that list.

The officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to freely discuss the negotiations, said the United States, the United Arab Emirates, which hosted the talks, and Israel together offered less than $1 billion, and much of it in fuel credit and promised investments, not in hard cash, which Sudan desperately needs with its currency in free fall and inflation spiking.

Sudanese negotiators had wanted at least double that in return for normalizing ties with Israel.

The State Department declined to comment on the talks. Israeli officials also declined to comment on the negotiations.

Demonstrators in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum last week protest a deal the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain agreed to with Israel to normalize relations. (Abbas M. Idris/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Bashir funded and funneled arms to the Palestine Liberation Organization, Hamas and others, which in turn led Israel to lobby the United States to place it on its list of state sponsors of terrorism. Osama bin Laden, who led al-Qaeda, also lived and operated openly in Sudan for years.

Those processes were slowly progressing when the Trump administration introduced normalization of ties with Israel as part of the equation.

“Linking the lifting of Sudan from the terror list with Israel normalization is pure blackmailing,” said one of the two Sudanese officials, a senior member of the civilian government. “The U.S. administration is potentially undermining the transitional government.”

In Sudan, as in the United States, Israel is a sensitive, emotional issue. When Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Sudan in September, Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok rebuffed the urging of the secretary to recognize Israel, saying his unelected civilian government lacked a mandate on such a delicate issue.

“Everything changed for Sudan when the UAE signed their agreement with Israel,” said Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and former chief of staff to the State Department’s special envoy to Sudan. “Up to that point, it was a fairly orderly process for Sudan to get off the terror list. That process had been delineated, and Sudan was assiduously ticking off requirements.”

“Normalizing ties with Israel is a highly controversial move that has not been sufficiently debated within the political mainstream in Sudan,” Hudson said. “Were it not for the U.S., this would not be a topic of public debate.”

The State Department holds sway over Sudan’s fate.

Pompeo has the authority to remove Sudan from the terrorism list, possibly unlocking billions of dollars in international funding, without congressional approval. Sudanese negotiators had hoped to get more than just delisting out of an Israel deal, however, arguing that Sudan needs at least $2 billion if not more to avert imminent economic collapse.

“The Sudanese have fallen into the trap of overestimating their value and not realizing that getting them off the SST list is important only to themselves,” said a U.S. official with knowledge of the talks who spoke on the condition of anonymity to comment on sensitive diplomatic discussions. “They’re likely to miss the window to make a deal and find themselves facing harsher terms.”

Hamdok, an economist and leader of Sudan’s civilian government, which shares power with a military council, has staked his credibility on promises to get Sudan removed from the terrorism list, as well as on preventing an economic meltdown. But the normalization of ties with Israel could threaten other strides he has made, such as the signing of historic peace deals with rebel leaders who fought protracted conflicts with the Bashir regime.

“I don't think the issue of Israel can be resolved without consensus,” said Yassir Arman, deputy secretary general of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement-North, which signed a peace deal with Khartoum in September. “It may create a divide between the transitional government and the public. We are looking for a decent discussion based on the interests of Sudan without any polarizations or accusations.”

Before the UAE and Bahrain changed their stance recently, only Jordan and Egypt in the Arab world had open ties with Israel. Attempts in the past to get other countries to do so have failed.

“No one wants a repetition of the 1983 Israeli-Lebanese peace agreement, which, signed by a Lebanese government without popular legitimacy, collapsed in less than a year,” Payton Knopf of the U.S. Institute of Peace and Jeffrey Feltman of the Brookings Institution wrote in a report last week.

Even if a normalization deal is struck, an additional hurdle remains for Sudan’s international relations to return to normalcy: Democratic leaders in the U.S. Congress are holding up legislation that would restore Sudan’s sovereign immunity, the legal doctrine that makes governments immune to civil suits, like that of 9/11 victims, or criminal prosecution. Sudan lost that immunity when it was put on the U.S. terrorism-sponsor list.

For now, officials in Khartoum and Washington remain skeptical that any deal will be reached before the U.S. election, meaning Sudan may stay on the list for months. For those who have worked to rid Sudan of that distinction, the stalled talks are a major setback.

“The new Sudanese government has worked hard to meet the requirements for delisting, going the extra mile by many counts,” said Ihab Osman, chairman of the U.S.-Sudan Business Council. “There is no doubt today that the Sudanese government has fundamentally changed and is looking to be a responsible and reliable regional partner in the global community.”

Bearak reported from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Mohieddin reported from Khartoum. John Hudson in Washington and Ruth Eglash in Jerusalem contributed to this report.