Tuesday May 14, 2019

By Murtaza Hussain

Abdikadir Mohamed felt nervous as he approached the customs desk at John F. Kennedy Airport on December 13, 2017. The previous summer he had married his wife, Malyuun, in a ceremony held in South Africa, and now he was on his way to Ohio, where she lived. Malyuun was pregnant with their second child, and Mohamed was anxious to be with her. He stepped to the counter clutching the one-year permanent residency document he’d been granted by the U.S. embassy in Johannesburg a few months earlier.

Although his papers were in order, Mohamed had reasons for concern. The political situation for immigrants in the United States had deteriorated under Donald Trump, and the U.S. Supreme Court had recently allowed his controversial “Muslim ban” to come into effect. Mohamed was a Somali national who had been living in South Africa as an asylum seeker; instead of a passport, he had a special travel document issued by the Red Cross. Although Somalis were one of the six nationalities targeted by Trump’s ban, Mohamed had received his U.S. visa before the measure had come into effect. As a result, he was technically free to enter the country.

And at first, all seemed to go smoothly. A Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer asked him a few basic questions, and after a short wait, he was handed back his travel document with the words, “Go, Mohamed,” indicating that he was free to proceed. Mohamed looked at his visa. It had an entry stamp on it, which validated his residency document. He had made it into the United States. He gathered his bags and left the counter. As he walked, the anxiety that had gripped him throughout much of the flight to the United States began to evaporate. In its place grew the excitement of seeing his family. The fear that had tormented him, of missing the birth of his child, seemed to be past.

It would prove to be a fleeting moment of relief. Little did he know, he was about to be flagged by a secretive enforcement arm of CBP focused on targeting passengers who have already cleared immigration. As a result, he was blocked from entering the United States and given the choice of being deported to Somalia or waiting in custody while he sought asylum. Seventeen months later, Mohamed remains behind bars at an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Elizabeth, New Jersey, subject to an asylum process that could drag on for years.

Mohamed’s troubles began as he headed to catch his connecting flight to Columbus, Ohio, according to immigration court documents and interviews with his lawyers. Two CBP officers stopped him, and one of them asked, “Are you from Mogadishu?” Mohamed replied that he was originally from Somalia. The officer asked him to unlock his phone and give it to him. He then told Mohamed that the agents wanted to talk to him briefly in an interview room, adding that it would only take 10 minutes. In front of Mohamed, the two officers exchanged words with each other about whether an interview was really necessary. They then told him to follow them to an interrogation room.

It would later emerge in court that Mohamed had been targeted by a branch of CBP called the Tactical Terrorism Response Team (TTRT). Little is publicly known about the TTRT, but the Department of Homeland Security website describes it as a team that subjects travelers who have already cleared immigration to extra scrutiny. “For FY 2017 to date, as a result of the dedicated efforts of the men and women serving on CBP’s TTRT, and the information discovered during secondary inspection, nearly 600 people who had been granted visas or other travel documents … have been refused admission to the United States,” indicates written public testimony from DHS officials given in May 2017.

Last year, then-commissioner of CBP Kevin McAleenan (who is now the acting head of DHS) similarly described the TTRT as a tool for denying entry to travelers who were not otherwise watchlisted. In an interview with a publication of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, McAleenan said that the TTRT “has been a tremendous success in identifying previously unknown individuals that present a security risk and in denying entry to folks that were not watch listed prior to their travel.”

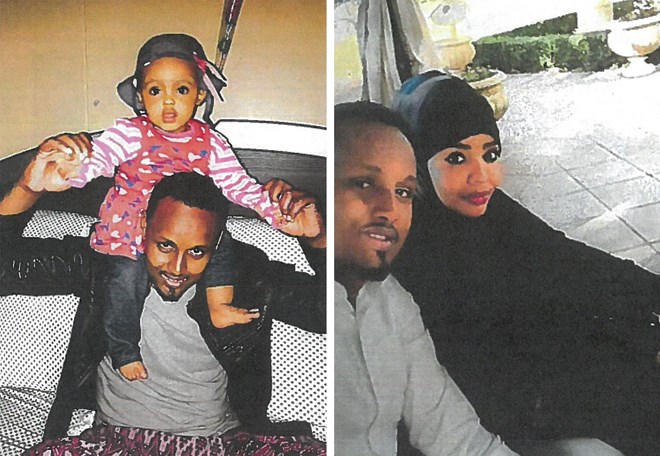

Abdikadir Mohamed with his daughter, left, and wife, Malyuun. Photos: Courtesy of the family

In the interrogation room, Mohamed was searched and questioned about his life in South Africa. His English was rudimentary, and he struggled to keep up with the interrogators’ rapid-fire questions. He asked for an interpreter twice but was told that his English was fine and that he should just answer “yes” or “no” to any questions. CBP officers went through his phone and found a press release from a political organization called the Ogaden National Liberation Front, an Ethiopian separatist group active in the Somali diaspora.

Despite its ongoing dispute with Ethiopia, the Ogaden National Liberation Front is not on the State Department’s list of designated terrorist organizations. The Ethiopian government also recently removed its terrorist label as part of a political reconciliation process in the country. Mohamed was questioned about the group and whether he had ties to it. What happened next is disputed, but according to Mohamed, he told CBP officers that he had no ties to the group. By this point, he had missed his flight to Ohio.

In an affidavit submitted during immigration proceedings, a CBP officer who interrogated Mohamed claimed that he had admitted to being part of the Ogaden National Liberation Front and that he should have disclosed that to the U.S. Embassy during the visa process. The officer also claimed that Mohamed had admitted to originally traveling to South Africa from Somalia on forged documents, and that he had no fear of returning to Somalia. He also indicated that he was part of the TTRT and that Mohamed had been randomly selected for an additional interview while at JFK. For his part, Mohamed denies admitting to having been part of the group and says that he had been unable to even understand the CBP officer’s questions after being denied a translator. In their exchange, Mohamed told the officer that he was from the Ogaden clan in Somalia, a larger ethnic grouping distinct from the Ogaden National Liberation Front.

After he was taken to a separate section of the airport, fingerprinted, and photographed, one of the officers who had detained Mohamed came back to speak to him. “Bad news,” the officer said. “I heard from my boss. You have to go back.”

Mohamed’s heart sank. Malyuun and his daughter were still expecting him that day in Ohio. Suddenly CBP was telling him that they were going to deport him. They gave him two options: South Africa, where he had suffered physical assaults by xenophobic gangs, or war-torn Somalia. Mohamed told the CBP officers that he wanted to speak to a lawyer. He was told that if he wanted to contest his deportation and seek asylum, he’d have to face an immigration judge. He was put in handcuffs and transferred the next day to the detention center in New Jersey. A parole request to be freed while his asylum claim was adjudicated was denied by ICE. Last May, he missed the birth of his second daughter.

“The government is bragging about stopping people from entering the country who had already gone through extremely onerous immigration and border control processes. Mohamed passed inspection by four CBP agents and then was stopped on the whim of an agent who was part of the TTRT and identified him as Somali,” said Tarek Ismail, a senior staff attorney in the Creating Law Enforcement Accountability & Responsibility (CLEAR) project, which is representing Mohamed alongside the Immigrant and Non-Citizen Rights Clinic at CUNY School of Law. “He did everything required by the law. Yet even though he was stamped in as a lawful permanent resident, he’s now languished in detention in separation from his family for the past 17 months.”

The allegedly random selection of Mohamed by the TTRT after he had already cleared multiple immigration checkpoints alarms activists focused on border issues, who have already developed a jaundiced view of CBP enforcement policies. To them, it seems more like profiling. “There’s no surprise that an institution created to enforce xenophobic policies would target immigrants from a country like Somalia. Black immigrants are among the most heavily targeted people in our community and [Mohamed]’s case highlights that,” said Darializa Chevalier, an organizer with Families for Freedom, a New York-based immigrant rights organization.

CBP did not respond to a request for comment.

In November 2018, Mohamed was admitted to the hospital. He had been complaining of chronic pain in his back and side over the past eight months. Shackled to a hospital bed, surrounded by guards, he underwent medical tests, and on a subsequent visit, doctors confirmed to him that he had developed a serious though noninfectious form of tuberculosis.

In response to a request for comment, an ICE spokesman said that “Abdikadir Mohamed, a Somali national illegally present in the U.S., is in ICE custody pending proceedings before the immigration court due to immigration violations,” and added, “ICE takes very seriously the health, safety and welfare of those in our care.”

An upcoming hearing in Mohamed’s asylum case is scheduled for May 21. Meanwhile, his detention in ICE custody continues.

“Abdikadir wanted to be here to work and help take care of the kids so I could continue school. Because he is in there, I had to drop out of college to work seven days a week,” his wife Malyuun told The Intercept. “Our oldest daughter is two years three months; she’s only seen her dad twice. This has been so hard for us as a family. We don’t want to be people who just work in warehouses or service jobs, we want to be educated people and raise our kids with a better life.”