Thursday August 15, 2019

By Robyn Maynard

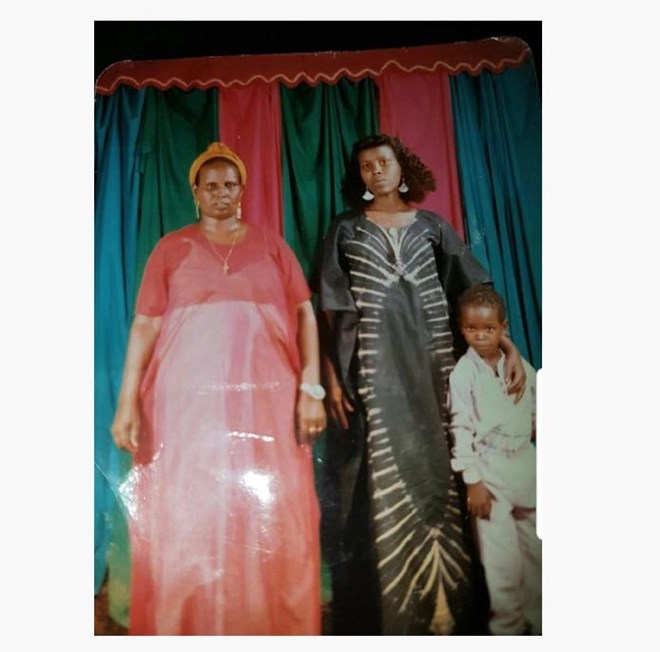

Abdilahi Elmi, far right, is seen in a childhood photo in Somalia, posing with his grandmother (left) and aunt (right), both now deceased. ABDILAHI ELMI FAMILY PHOTO

Canada is failing Abdilahi Elmi, a Somali former child-refugee who is facing deportation to Somalia on Wednesday. Elmi’s case, in fact, is one that demonstrates how Black people — especially those without citizenship — continue to be subjected to multiple forms of state neglect.

Elmi arrived in 1994 as a child refugee, at the age of 10, after living in a refugee camp with his grandmother for several years. A few years later, he was removed from his family home and placed in state care. Elmi ended up living on the streets by 16 and became involved in the criminal justice system, in part, he has noted, due to substance use issues that he is now working to manage.

The situation of Elmi, now in detention in Edmonton, mirrors those of other Black young people in Canada: a report by the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies notes that Black young people involved in state care are disproportionately impacted by “homelessness, unemployment and involvement with the criminal justice system.” These outcomes, the Ontario Human Rights Commission has noted, are indicative of systemic racism spanning a multiplicity of institutions, resulting in a “child-welfare to prison pipeline.”

In Canada, where government statistics note that just over half of Black residents were born elsewhere, it is becoming clear that this pipeline often extends, too, into the immigration system, becoming a child-welfare to prison to deportation pipeline.

The reason that Elmi faces not only incarceration, but deportation, is the result of neglect within the provincial child welfare system: Elmi was a refugee in state care, but the agency that was responsible for him did not apply for his citizenship status. Because the state failed Elmi in this regard, he has been living as a refugee for 24 years.

On June 26, the Canada Border Services Agency deemed Elmi inadmissible as a result of his involvement with the criminal justice system: a clause in Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) states that any non-citizen with a sentence over six months may be deemed inadmissible to the country. This clause is wrought with its own injustices, but it wouldn’t have impacted Elmi had the child welfare system done its job.

Elmi’s case is not the first time a child refugee was left — by the state — without legal protections only to later face possible deportation. His situation bears striking similarities to those brought forward in last year’s #FreeAbdoulAbdi campaign.

This campaign, led by Abdoul Abdi’s sister Fatouma, El Jones and others, successfully halted the deportation of Abdi, also a Somali former child refugee who had been caught up within the criminal justice system. He, like Elmi, faced deportation due to the state’s failure to apply for his citizenship status when he was in their care.

At the time, Benjamin Perryman, then Abdi’s lawyer, stated: “If the state is going to apprehend children, it has a responsibility to care for them. That includes non-citizen children.” Abdi’s deportation was overturned and the victory resulted in shifts in child welfare policy in Nova Scotia, where Abdi had been in care.

But Elmi’s case shows that despite Abdi’s victory, too little has changed for those whose lives exist at the intersections of the child welfare, criminal justice, and immigration systems. Abdi faces deportation to Kismayo, Somalia, his mother’s hometown, and advocates say that he fears for his life. Elmi does not speak Somali or have any family connections to the country. Kismayo is also the location where Somali-Canadian journalist Hodan Nalayeh was killed, alongside 25 others, on July 14.

Elmi’s case, important in its own right, also resonates because it exposes a broader pattern of systemic state neglect facing Black youth in care that is impacting Black young people’s ability to remain in the country.

Abdilahi Elmi deserves to stay in Canada — and no more children should grow up to face his situation. Not only should Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale cancel Elmi’s deportation order, but provinces should mandate provincial child welfare agencies to apply for immigration status for all refugees in state care.

Further, to avoid further cases like Elmi’s, the federal government should work with the provinces to retroactively grant status to all refugees who were wards of the state and remain without citizenship.