Tuesday April 30, 2019

BY SELIM KORU

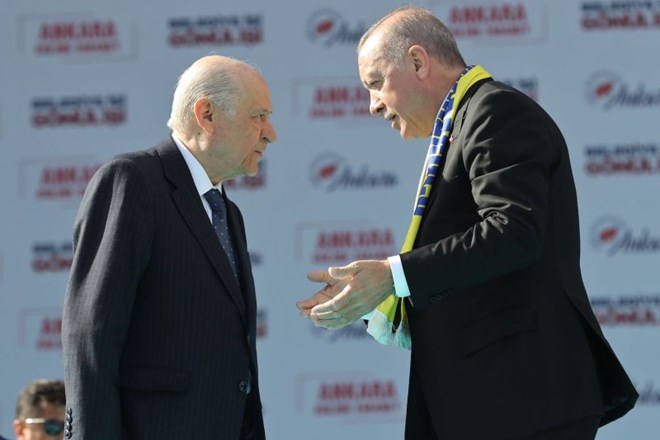

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (R) and leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) Devlet Bahceli talk on stage during a rally in advance of local elections in Ankara on March 23. (ADEM ALTAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

The president’s coalition partners aren’t pulling him to the right. They’re doing his bidding.

A recent Foreign Policy essay by Selim Sazak argues that Devlet Bahceli, the leader of Turkey’s Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), “holds all the cards” in the alliance between his party and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). Sazak also argues that Bahceli, in general, is “pulling Erdogan to the right.” All this makes Bahceli “the most powerful person in Ankara.” It’s a counterintuitive but seductive argument, and Sazak is by no means alone in making it. There have been many reasonable commentators in Turkey and abroad who have put forward a similar narrative.

The idea is appealing; it implies that if only the AKP government could get away from the so-called ultranationalism of the MHP, things could go back to the way things were in the early 2010s. Turkey could restart its peace process with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), even stop threatening the PKK’s offshoot in Syria, the U.S.-allied People’s Protection Units. Many of Washington’s problems would be solved, so the logic goes, in one fell swoop.

But the logic is faulty. Erdogan is not being pulled anywhere. He is in firm control of his relationship with the MHP and his government’s actions.Erdogan is not being pulled anywhere. He is in firm control of his relationship with the MHP and his government’s actions. Nor is Erdogan inhabiting an ideological space or policy position that is alien to him. He is still where everyone always wants to be: at the top.

The bond between the AKP and the MHP is officially called the “People’s Alliance,” but this is a misnomer. Alliances are usually formed between comparable entities—such as sovereign states, or political parties subject to the same rules. This is not the case in Turkey’s governing coalition. Erdogan’s AKP is not a mere participant in a game of democratic politics but the vehicle for the redesign of Turkey’s political regime. By definition, it cannot have partners, just subservient political organizations. The MHP is the largest such organization, but it’s not the only one. The Great Unity Party, an MHP splinter group created in 1993, was part of the alliance in the 2018 elections. Erdogan has also flirted with the idea of arranging for a small Islamist outfit to peel away votes from the Islamist opposition Felicity Party.

The Erdogan government subsumed the MHP sometime around early 2016, when it was at its weakest point. The November 2015 elections had been a humiliating defeat for the party; it lost nearly half of its seats in parliament, ending up with significantly fewer than the Kurdish left-wing Peoples’ Democratic Party. A rebellion had sprung up within the party, led by Meral Aksener, who had served as interior minister in the 1990s, as well as several other party grandees. The rebels wanted to change the leadership through extraordinary congresses, and they collected more than the required number of signatures to do so.

This should have been a simple legal procedure, but their case was blocked in court, and Bahceli purged the party to make future attempts impossible. Meanwhile, the mainstream press loyal to the government smeared the rebels, labeling them agents of Fethullah Gulen, Erdogan’s ally-turned-enemy. In subsequent months, Bahceli began to visit Erdogan more frequently at the presidential palace.

In 2017, Turkey held a referendum to amend the constitution and create a super-presidency custom-made for Erdogan. The MHP for the first time openly supported the president, pushing him just barely over the 50 percent threshold. Then, simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections were scheduled for November 2018, but an economic recession was taking shape, weakening support for the government. By the spring of 2018, everyone in Ankara was talking about early elections. The only problem was that Erdogan had never called for early elections, considering it a sign of weakness.

Luckily for him, Bahceli stepped forward to say that early elections were necessarily to “disrupt the game of those playing for chaos.” Erdogan promptly invited his coalition partner to a “summit.” After only half an hour, they had agreed to hold elections in June, earlier than anyone had expected. Bahceli voters got to feel like their candidate was more than a stooge; Erdogan voters got to feel like their leader actually listened to other human beings.

Heading into the 2018 parliamentary elections, the MHP was significantly diminished. The rebels of 2015 and 2016 had formed the Iyi Party (literally meaning the “Good” Party), and it looked like they were going to take the bulk of the 10 to 15 percent pan-Turkic nationalist vote. This would put the MHP below the 10 percent electoral threshold to enter parliament, so the Erdogan government passed a controversial law to allow parties to band together into so-called alliances and overcome that hurdle. The Erdogan government was betting that its opponents would be too divided to take advantage of the law.

What happened next is what animated the myth of the all-powerful MHP. The MHP’s 11.9 percent nationalist vote in 2015 self-replicated in 2018: The party got 11.1 percent, while its splinter Iyi Party got 10 percent. This shouldn’t have been surprising. At the height of the AKP’s rise in the 2000s, many MHP voters switched over to the party but retained an affinity for their old home.At the height of the AKP’s rise in the 2000s, many MHP voters switched over to the party but retained an affinity for their old home. By the 2018 election, it had become clear that the MHP was now in the fold of the Erdogan government, so those people simply split their tickets and voted for the MHP in parliament and Erdogan as president. A vote for the MHP was still a vote for Erdogan, a different brand name for the same product.

Still, the MHP looked so good after the election that some of its members of parliament began to believe that they could influence government policy and called for a pardon for the notoriously pro-MHP mafia leader Alaattin Cakici. Erdogan flatly rejected the proposal, a short spat ensued, and the MHP backed down.

Then, in last month’s regional elections, the MHP was a tool of the AKP’s carefully crafted strategy. Erdogan’s government carries out granular polls across the country and probably tried to optimize its gains by placing the MHP in provinces where their candidates had a better chance. As a result, it’s true that the MHP has punched above its weight, mostly by winning in sparsely populated conservative municipalities. But the AKP’s planners must be thinking that if they hadn’t passed the law to enable alliances and carried the MHP in the 2018 elections, they wouldn’t have forced the opposition to band together—and if the opposition hadn’t done that, it might not have taken large cities away from Erdogan, including Ankara and Istanbul, in the recent regional elections.

Still, the Erdogan government appears to value the MHP as a way to push its wares under the brand name of pan-Turkic nationalism, as well as to obfuscate the optics of one-man rule. This does not mean that Bahceli has significant leverage over Erdogan. Sure, he could leave the governing coalition and rejoin the wilderness of opposition politics. It would be a short-lived expedition, however, and would very likely end the septuagenarian’s political career.

The Erdogan government and the MHP may be ideologically different, but they are temperamentally compatible.The Erdogan government and the MHP may be ideologically different, but they are temperamentally compatible. To understand the relationship, it’s worth dipping into the recent history of the Turkish Islamists.

Erdogan is often referred to as an Islamist, but that is an oversimplification. Turkish Islamism can roughly be divided into two camps. There is the orthodox tradition that largely feeds off of the foreign classics of Islamism, such as Sayyid Qutb and Abul Ala Maududi. This brand of Islamism is rather prescriptive, and it’s a political ideology in the strict sense of wanting to find a mode of governance.

The other camp is the romantic Anatolianist tradition, which can be traced to Turkish poets, historians, and polemicists during the Cold War, such as Nurettin Topcu. This wing was relaxed about Islamic doctrine and more concerned with aesthetics of political revolt. They were eager to publish magazines, stage plays, and throw themselves into political debate.

Most Turkish Islamists are a mix of orthodox and romantic. Those closer to the orthodox end reject the MHP because they see a contradiction between Islam’s ban on ethnicity-based politics and the party’s pan-Turkism. For Anatolianists, it is a more complicated relationship. Like many romantic movements, they saw the nation as a pure entity. Their youth movement, the National Turkish Student Union—to which Erdogan, former President Abdullah Gul, and many of the AKP’s other founders belonged—at times sided with the nationalists during the 1970s, when university campuses saw clashes between leftists and nationalists.

MHP-style nationalism was still seen as a low pursuit and had to be discouraged whenever possible, but it could be worked with. Islamists today don’t like to talk about it, but for a spell in the 1970s, Necip Fazil—their most revered poet and Erdogan’s personal hero—actively campaigned for the MHP. Tanil Bora, a scholar of the Turkish right, put it best when he wrote that the Anatolianists “drew a solid route between Islamism and nationalism.” Erdogan’s government today continues to travel comfortably along that route.

These ideological differences are not very important today. Sure, there might be small changes if the hierarchy within the Turkish right were different. Under the AKP, the government funds jingoistic TV shows about Abdulhamid II, the proto-Islamist sultan of the late Ottoman Empire. Under an MHP-dominated hierarchy, it would have probably been a similar TV show about the nationalistic Young Turks who deposed him.

The AKP tried to make peace with the PKK and branded them enemies of the nation once it failed. An MHP government would have ended up in the same place without the detour.The AKP tried to make peace with the PKK and branded them enemies of the nation once it failed. An MHP government would have ended up in the same place without the detour. The Turkish state under the MHP would still pursue an increasingly bellicose foreign policy, would still be obsessed with Western predominance, would still revere all things “national,” and would still define itself against all things “anti-national” or brand them with the new bogeyman of right-wing columnists the world over: “globalism.”

If the Erdogan government’s current stance really were an accident of electoral calculus, it would not be so prevalent across the world. India, too, is ruled by a macho strongman denouncing his political opposition as “anti-national” fifth columns, speaking of an epic economic and military revival, and making a spectacle of the wars he wages against armed insurgencies. China is powerful enough to intern around a million of its people who don’t fit its idea of “national.” Under Russia’s president, critics have been killed with impunity. All of these regimes invest in flashy news programs and TV shows that perpetuate narratives of national revival and, eventually, revenge against Western dominance. All of them ride the wave of technology, global capital, and massive migration.

The Erdogan government and the tens of millions of Turks who support it are part of this global tide because they want to be. The MHP is not pulling an otherwise centrist government into ultranationalism. The corollary—that a separation of the AKP and the MHP would somehow make the Erdogan government more palatable—also doesn’t hold. The MHP isn’t very important in this picture. It is a small fish in very big pond.

Selim Koru is an analyst at the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey (TEPAV). Twitter: @SelimKoru

This article is republished from Foreign Policy