Sunday December 2, 2018

Francesca Mannocchi in Tripoli

Libyan forces loyal to the Government of National Accord keep watch from a position south of Tripoli. Photograph: Mahmud Turkia/AFP/Getty Images

They risked their lives under Gaddafi – and are appalled by the country’s new tyrants. In a city of Islamists and warlords, Libya’s dissidents speak out

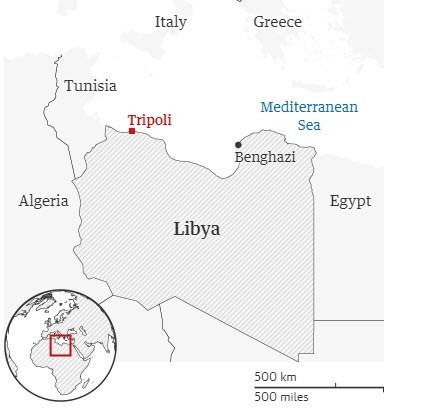

The drive through the southern outskirts of Tripoli takes frightened travellers past the devastation caused by the latest battle between the militias over the wreckage of Libya’s civil war.

There are smashed homes and rubble-strewn streets left by the blasts of tank and rocket fire during fighting in September. Some compare militia-dominated Tripoli with Al Capone’s Chicago but the comparison is false: Al Capone never had access to heavy artillery.

Meeting opponents of Libya’s government these days is no easy matter. Doing so means slipping past the official minder assigned to me in a Tripoli hotel, getting out into the street and into a car parked discreetly around the corner. From there, it is a long and elliptical drive through the city’s backstreets, the driver performing cutbacks and sudden turns to shake off a tail.

Seven years after Muammar Gaddafi was deposed and killed in the Arab spring revolution, Libya has gone full circle from dictatorship through revolution, democracy, chaos and back to a new kind of tyranny. Except this time there is not one dictator but dozens, in the form of the very militias who defeated him. Also back are the dissidents, and after several days of hushed phone calls I have a meeting with one of the most prominent, Hmeed al-Mahdi, a lawyer.

Driving through this city means navigating a political fog as you try to work out who among the rag-tag gunmen in assorted uniforms and battered pickup trucks are gangsters, and who constitute the official security forces of the United Nations-backed government. After a while you realise they are the same. One unit is freshly kitted out in smart blue uniforms of the interior ministry, but it remains a militia, as violent and threatening as before. Tensions are high after the body of one warlord was dumped by rivals outside a city hospital in the latest tit-for-tat killing.

I meet Mahdi at his home, which he rebuilt after it was burned down by Gaddafi thugs as punishment for his opposition. Now he has reinvented himself again as a dissident, opposing the new tyranny he describes as “a country of chameleons”.

Smoke rises during clashes between different armed groups in Tripoli in September. Photograph: Hani Amara/Reuters

Fresh from Friday prayers, he meets me wearing an elegant white jalabiya robe and offers a glass of highly sugared tea. “We killed Gaddafi, but many small dictators, the militia leaders, were born from the ashes of his corpse,” he says.

In another country, or another time, Mahdi’s house would have a blue plaque on the wall outside, denoting the historical significance of the place where the dissidents met, risking everything to dream the dream of freedom. We sit in the room where in the Gaddafi years the activists would talk and plan. “This room was called the protesters’ hall,” he says with a grin. “This is the place in the house that is dearest to me.”

Gaddafi’s regime was brutal and Mahdi was beaten and thrown into jail. Yet even in jail he nurtured the hope that Libya would one day be free, a hope that is dying as the fruits of freedom become clear.

“We did not ask to torture and humiliate a dictator so we would become like him. Where has this bloodshed brought us? To a daily hell.” Then he lowers his eyes: “I think the revolution was a mistake.”

The UN proclaimed three years ago that the hell Mahdi describes would end with the creation of the government of national accord, parachuted into Tripoli to rid it of gangsterism. But far from expunging the militias, the government is beholden to them.

Tripoli’s warlords are on the state payroll, through the simple expedient of gunmen threatening the bankers with kidnapping or worse. Similar pressure resulted in the government handing its all-important intelligence and surveillance portfolio to an Islamist militia. Even as militias fight each other in the capital, they also fight the army of the nationalist warlord Khalifa Haftar, a brooding presence far to the east.

A fighter loyal to the internationally recognised government fires during renewed clashes in Tripoli in September. Photograph: Mahmud Turkia/AFP/Getty

Meanwhile, the citizens suffer: there are shortages of petrol, electricity, water and banknotes. Libya is rich, with £50bn of foreign reserves and booming oil production. But only a handful of banks – those controlled by militias – are permitted to dispense cash. Citizens form kilometre-long queues to collect it.

My excursion to meet Mahdi is a rare breath of fresh air in a city where information is tightly controlled. In the Gaddafi era visiting journalists needed a permit just to step out of their hotel. Now I need two – one from the government, the other from the militia controlling whatever district I plan to visit. Nobody elected this government, which was appointed by a UN-chaired commission, and it has two faces for the world. One is for visiting western diplomats, who make occasional visits to the city to be photographed smiling with the prime minister. The other face is for Libyans themselves, and it is not pretty.

“Don’t take pictures of the bank queues. Don’t interview the people there,” says my government minder, Ishmael. His orders are to follow me everywhere, clutching a mass of permits and permissions, and this has a faintly comic aspect. I can buy coffee at one of the city’s ubiquitous coffee bars, but I can’t talk to the customers as I have no permit.

Nor can I talk to the thuggish young men, little more than boys, lolling outside. They wear expensive branded clothing and play with machine guns, clustered around their shiny black Mercedes. They know they are the true power in this city, and so does everyone else. In frustration I ask Ishmael what reporting I can do, with no permits to talk to anyone. “I don’t know, maybe nothing,” he says.

Another dissident is Ibrahim, a radio presenter who has formed a little band of like-minded souls called the crisis committee. They hold earnest meetings to debate the way ahead, which are either noble or futile, depending on your point of view.

The electoral commission headquarters in Tripoli were attacked by suicide bombers in May. Photograph: Mahmud Turkia/AFP/Getty Images

Ibrahim tells me Gaddafi-style media censorship, insidious and sinister, has returned: “We can criticise the government, the UN or Haftar, but there are two things it is better not to talk about. The militias, and the bearded ones [Islamists].”

Several TV stations have been burned down because they failed to understand these instructions and a dozen more now broadcast, for safety, from abroad.

All of which makes Ibrahim think Libya can’t handle freedom. “We weren’t ready for revolution,” he says. “We didn’t have the means to deal with that freedom. We were like a child who had asked for a toy for a long time, and then finally got it. But the toy was disassembled and we didn’t know what to do with the pieces.”

Tripoli’s bureaucracy is mostly run by the same people who ran it under Gaddafi, and many are gleeful about the return of old ways. “We are all green in this office,” boasts one media officer, a reference to the dictator’s green flag. “We know how to treat journalists. They are all spies.”

And then there is the corruption. Under Gaddafi it was widespread, but centralised. Now it is chaotic. Mohammed, a 35-year-old who does evening shifts at my hotel, tells me Tripoli has corruption on every level but he no longer bothers to report it. “Those to whom I should denounce the corruption are as corrupt as others,” he says. “Probably more.”

In the revolution Mohammed picked up a gun and joined the rebels, but says now it was a mistake: “If I could, I would erase those days from my memory. I know Gaddafi was a dictator, but we were not ready for democracy.” The unlikely beneficiary of this mood of resignation is Khalifa Haftar, whose forces are built around Libya’s regular armed forces. A former Gaddafi ally who later turned against the dictator, Haftar accuses the new government of being beholden to Islamists and has vowed to march on Tripoli and crush the militias. Many support him, despite their fears that he wants military rule.

A rare opinion poll, commissioned by a US government agency, found his army the most popular Libyan institution, its 68% support eclipsing the government’s 15%.

Mohammed explains the sentiment. “Now we are all just resigned, and in this resignation many of us think, with pain in our hearts, that it is better to have Haftar. It is better to have a strongman back.”