Tuesday July 11, 2017

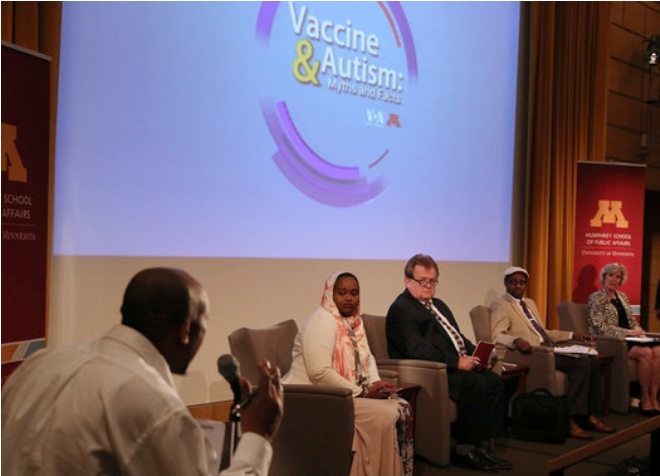

Abdirisak Jama, left, who said his child didn’t have autism until he was vaccinated, told his story and raised concerns to a panel of experts during Saturday’s town hall on vaccines and autism.

The Twin Cities area has recently experienced the most severe outbreak of measles in decades. Most cases occurred in the Somali community, where we’ve also seen the sharpest decrease in vaccination rates. Concerns about the relationship between vaccinations and autism run deep in this community, fueled by misinformation about a perceived increase in the incidence and severity of autism. For now, the measles outbreak has subsided without erupting into a major health crisis, but we cannot be complacent. We need more open communication about prevention, more resources to support families and a greater sense of urgency around questions being posed by the Somali community.

Last weekend, the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs partnered with Voice of America to host a town hall on myths and facts surrounding vaccines and autism. About 200 people attended in person, and several thousand participated live via Facebook. The majority of attendees were Somali community members, many of them parents of children with autism. Clearly, this is an emotionally charged issue for all who care deeply about the well-being of their children.

And that is just the point: The decision on whether or not to vaccinate one’s son or daughter is rooted in parents’ deepest desire to do the right thing for their children.

When evidence overwhelmingly suggests that vaccinations are our best bet for avoiding devastating outbreaks of preventable diseases like measles, and when assertions that vaccinations cause autism have been debunked, one might wonder why a parent would make the decision to forgo vaccinations. If we seek to deepen our cultural and contextual understanding of that decision, those of us who have vaccinated our children would better understand this unsettling choice. An increased level of empathy may be the best preventive medicine of all.

A recent study conducted by the University of Minnesota’s Institute on Community Integration examined autism prevalence in Minneapolis and found a slightly higher incidence of autism among Somali children (about 31 per 1,000 children) than among their white peers (about 28 per 1,000). Significantly, the study found that Somali children with autism are more likely to also have an intellectual disability.

Further, the study observed that the stigma of autism in the Somali community is intense. One Somali parent said, “In our culture you are either sane or you are crazy. There is no gray area. There is no Somali word for autism.”

We would all be well-served to recall this country’s not-so-distant history of stigmatization, institutionalization and mistreatment of people with developmental disabilities.

In 1960, then-U.S. Sen. Hubert Humphrey and his wife, Muriel, became grandparents to a child with a severe developmental disability. Victoria Solomonson was born with Down syndrome on Election Day that year. The family ignored medical advice suggesting they institutionalize their granddaughter. Instead, Vicky was an active member of this very public family that, despite the privileges that came with their status, likely experienced the sting of social stigma.

When Humphrey, who went on to advocate for spending on special-needs programs and equal treatment under the law, observed that “the essence of true statesmanship is not a rigid adherence to the past, but a prudent and probing concern for the future,” I’m confident that the well-being of children — with or without disabilities — factored significantly into his vision. And I believe Humphrey would have us focus today on supporting families in the Somali community as if each child were his own granddaughter.

In that vein, medical professionals must show empathy while communicating clearly to parents that vaccinating children is absolutely essential. The health of the child and the health of the community depends on it.

At the same time, as neighbors and community members, we need to listen more and seek to better understand the fears and concerns parents are expressing.

Finally, policymakers and public-health researchers must demonstrate a sincere determination to seek answers to questions surrounding the incidence of autism in the Somali community. We must acknowledge that parents have honest concerns about what is happening in their community and with their children.

We must bring a level of urgency to supporting families and addressing these concerns as if we ourselves were that worried mother or father; as if each child diagnosed with autism was our own.