Seven Days

Wednesday April 19, 2017

By Kymelya Sari

Haji, left, arriving in Vermont in 2003. Courtesy of the Burlington Free Press

When Aden Haji was 8 years old, he and his family were on the cover of the Burlington Free Press. Haji and his parents, two siblings and uncle were the first Somali Bantu refugees to resettle in Vermont, on July 23, 2003. They left their refugee camp in Kenya and traveled for two days before arriving at Burlington International Airport, where a welcoming party greeted the family and gave them small American flags.

Reporter Candace Page wrote, "The men and boys wore drab gray sweatshirts with the initials of the U.S. refugee program on them, but [Haji's mother] lit up the airport with her blue dress, bright yellow head scarf and the scarlet cloth with which she held the baby close to her body."

Fourteen years later, Haji, now 22, stared goggle-eyed at the family photo during a recent interview. "Oh, wow!" and "That's crazy," were all he could say. The junior at the University of Vermont hadn't known about his family's historical significance in the state. Nor was he aware that their arrival had been immortalized in the local press.

When Seven Days met Haji's family days later, they were just as enthralled by the photo. The passage of time hasn't diminished family matriarch Asha Abdille's penchant for wearing brightly colored cotton dresses favored by traditional Somali women. She recalls being "a little bit scared" when the family arrived in the U.S. because she didn't speak English. She and her husband were unable to get a formal education in Africa, but she held hopes that her children would have a better future in Vermont.

The importance of getting a college degree isn't lost on Haji. "I'm getting an education to help lift my family here and in Kenya," he said. But the anthropology major isn't content to focus just on academics. At the UVM Mosaic Center for Students of Color Spring Awards Banquet on Friday, April 21, Haji will receive the Lufuno Tshikororo Award. It recognizes an undergraduate student of color who has demonstrated emerging leadership at the university.

While the award is a testament to Haji's role on campus, his community involvement started years earlier. He participated in an antidiscrimination protest at Burlington High School. He gave speeches on equity and youth activism during events to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. Day. He gave youth perspectives on problems that parents were trying to solve. Last year, Haji won the Ignite Burlington student-speaking contest, an event sponsored by the Hergenrother Foundation.

These days, he leads a mentoring group for multicultural youth at the Boys & Girls Club of Burlington that he named "Building Blocks to Success."

"Growing up, I realized I would have benefited a lot more if I'd had a mentor or someone to look up to," said Haji. "[Someone] who has gone through the same experience I've gone through, someone who has a cultural-rich background such as I."

Haji's transformation from a "very quiet, very reserved" boy to a "role model" hasn't gone unnoticed, said Bobby Riley, principal of the Integrated Arts Academy at H.O. Wheeler. Riley was the school librarian when Haji was a student there. The latter remains connected with the IAA community, and his siblings attend the school, Riley noted. Haji's "quiet leadership has rubbed off on his siblings," he said.

"That's what the Old North End needs," Riley continued. "Young men that are really positive, [who] create those connections and partner with young people; [they] help make some good decisions."

"He's a thinker," said Infinite Culcleasure from Parents & Youth for Change, a group that aims to improve educational opportunities for youth and families in Burlington and Winooski. "We don't have many nonwhite young men who are appreciated for that."

Haji sees the positive in everything. His mother described him as "a happy child." In an autobiography that he hopes to publish someday, Haji wrote that life in the refugee camp where his family lived was "simple and joyful." But the reality was far from it.

The Bantu refugees were ethnic minorities brought to Somalia from southeastern Africa as part of the slave trade some 200 years ago. Even after slavery ended, the Bantu continued to face persecution. When a civil war broke out in Somalia in 1991, they bore the brunt of the violence and fled to refugee camps in Kenya. By most accounts, life in the camps was difficult.

But it wasn't the harsh living conditions that Haji remembers. Having few possessions enabled him to nurture his creativity, he pointed out. He made toy cars from wires. He rolled a tire along the ground with a stick. "Coming from nothing, your mind is encouraged to find ideas to occupy yourself," Haji said.

When they first arrived in Vermont in 2003, Haji's mother hid at home, while the other family members were at work or school. The foreign language and culture terrified her, she admitted.

At the same time, her eldest son was trying to assimilate into his new environment by imitating the habits of his classmates. "I felt my priority was to fit in," Haji said, which included bringing lunch to school.

"Most of the popular students, they were all bringing their own food," he recalled. "I would make my own [turkey] sandwiches and salads." His parents were amused and wondered why he was eating grass, Haji said with a laugh. His parents bought him a lunchbox, which he attached to his backpack "so people could see.”

Like most of his peers, when he was an adolescent, Haji never saw himself as part of the bigger Burlington community. He said he thought, "I just live here ... and my voice does not count." There was no one from his community whose behavior he could model. "It was just hard to find someone who builds up their voice and who could show us how they did it," Haji said. It wasn't until he was a high school sophomore that he started to develop a sense of identity.

Haji's first foray into activism was in 2012. He was one of several English-language-learner students at BHS who staged a protest in response to racism in the district. Looking back on that experience, one of the organizers, Jacques Okuka, explained, "We wanted to feel included."

Now a junior at Southern New Hampshire College and still Haji's best friend, Okuka said he and his fellow immigrant students faced multiple struggles while growing up. Not only did they have to learn a new culture and language, they also struggled to reconcile their parents' customs with their desire to be like their peers.

"[The school administrators] don't understand the heavy load we carry as immigrants," Okuka said.

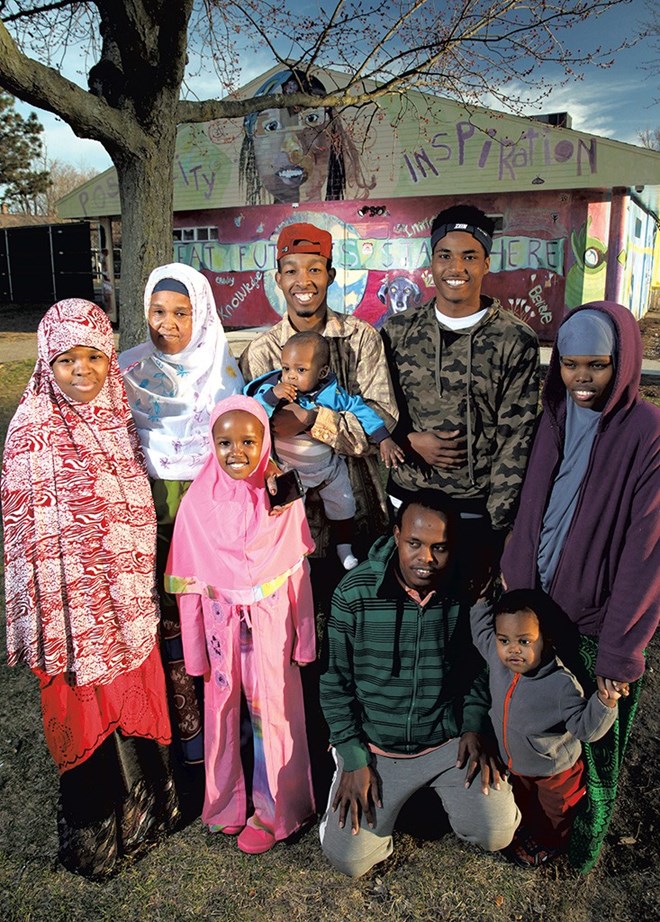

Aden Haji (back row, red cap) with his family. PHOTO: Matthew Thorsen

During high school, Haji joined the multicultural youth group Diversity Rocks and got to know Culcleasure. They later worked together with Parents & Youth for Change. Culcleasure, PYC's lead organizer and project manager, described the organization as an "intergenerational group of everyday people who have historically not had meaningful influence on political and economic decisions."

Youth involvement was uncommon at that time, Culcleasure noted. "When other people see Aden doing this kind of work, it makes it safe for [them] to do it," he explained.

But what impressed Culcleasure was Haji's authenticity and empathy. "He actually cares about other kids. It's not résumé-building for him."

Over time, Haji also began to feel comfortable giving media interviews about the causes he was promoting.

Today, Haji and Okuka, along with six of their peers attending college, are mentors to 21 youth, most of whom are people of color. During the school year, half of their interactions take place on Facebook because some of the mentors, including Okuka, reside out of state. "[Multicultural] youth don't realize how unique they are. They just want to fit in," said Haji, who was once in their shoes.

The mentors aim to help the youth develop their own identities and cultivate a sense of belonging, as well as achieve academic success. "We know their struggles," said Okuka. "It's easier for them to relate to us."

It's not only the youth who have benefited from their mentors' experience and connections. Since being a part of the group, Okuka said he feels a greater sense of responsibility toward the younger generation. "I have to represent myself the way I want these kids to represent themselves," he observed.

Next month, Haji will facilitate a workshop during the Multicultural Youth Leadership Conference organized by Spectrum Youth & Family Services. He hopes to invite New Americans to tell their stories, and then connect their stories to books and autobiographies of famous personalities. Although the junior admits he's got a lot on his plate, he's not slowing down.

"I love doing work that revolves around cross-cultural interaction, advocating for inclusiveness," he said, "just making [others] aware of Burlington's hidden minority communities."

Correction, April 19, 2017: The print version of this story misstated the date that Aden Haji and his family arrived in Vermont. They landed at Burlington International Airport on July 23, 2003.