Sunday July 10, 2016

By Adam Taylor

Afghan refugee Shazia Lutfi, 19, peeks through the door of her room at the former prison of De Koepel in Haarlem, Netherlands, on May 7. (Muhammed Muheisen/AP)

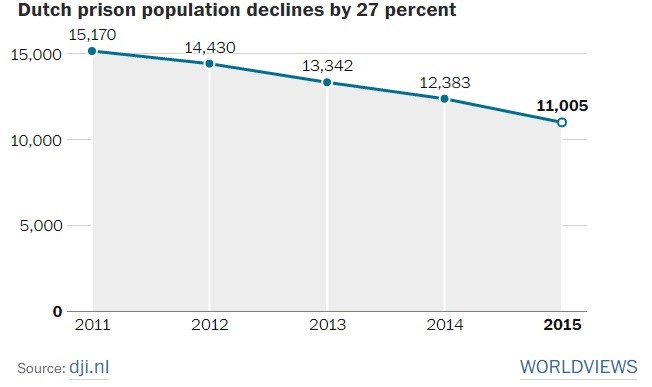

If you were to visit a prison in the Netherlands anytime soon, you might find it surprisingly empty. Just this week, the Dutch Justice Ministry announced that the total number of inmates held in Dutch prisons fell by 27 percent between 2011 and 2015. To put the Dutch situation into an American context, a 27 percent drop in the U.S. prison population would mean the release of almost 600,000 people.That's roughly the population of Milwaukee.

The situation in the Netherlands would seem to buck a broader and longer global trend of rising prison populations. In February, the Institute for Criminal Policy Research published a report that estimated the world's prison population had grown by almost 20 percent between 2000 and 2015, a margin above the 18 percent growth in the general population during that period.

In its own report, the Dutch prison ministry notes that it now has one of the lowest incarceration rates in Europe, with 57 out of 100,000 citizens imprisoned, second only to Finland at 54 per 100,000. England and Wales had the highest in Europe at 148 per 100,000, the report noted, though even that lags far behind the rate in United States, which was recently estimated at 693 per 100,000.

The latest decline in the Dutch prison population can be attributed to both a changing environment and changing tactics. The country's crime rate has dipped by about 0.9 percent a year during the past few years. At the same time, there has also been a switch toward using community service sentences and ankle-bracelet monitoring systems. These changes have led to an especially notable drop in the number of under-17-year-olds placed in youth detention (55 percent) as well as 18- to 22-year-olds placed in the general prison population (44 percent).The decline in the use of prisons has led to the closure of a number of them. In 2013, 19 prisons in the country were shut. In March, De Telegraaf reported that a further five were likely to close. Meanwhile, prisons that sit empty have been put to different uses. The country has rented out unused prisons to the Norwegian and Belgian governments to house their own prisoners. Some empty prisons have even been used to house refugees and migrants.

"The rooms are intended for one or two people, there are often gyms, a good kitchen," Janet Helder, a board member with the Dutch government agency responsible for housing asylum seekers, told the Associated Press earlier this year. "So in that sense, they tick many of the boxes we are looking at."

However, it's not necessarily just good news. If nothing else, the closure of prisons creates complications for those employed in the prisons. De Telegraaf reports that the closure of five prisons this year would make 1,900 people redundant and that a further 700 would be found jobs elsewhere. There's also considerable debate in the Netherlands about whether there are truly fewer criminals at work or if policing reforms over the past few years have led to fewer criminals actually being caught.

"If the government truly worked to catch criminals, we would not have this problem of empty cells," Socialist Party member of parliament Nine Kooiman said in March.

The Netherlands isn't the only country seeing a dip in prison populations. Sweden's prison population fell from 5,722 in 2004 to 4,500 in 2014, and the country has also had to close some underused prisons. Experts who spoke to the Guardian in 2013 suggested that the humane and comfortable nature of Swedish prisons had led to a better chance of rehabilitation for prisoners.