Friday, November 18, 2016

THE brutal term “failed state” was almost invented for Somalia. Since 1991, when its military dictator was overthrown, it has had no government that fully controls the country and no election worthy of the name. A fanatical jihadist movement known as al-Shabab (“the Youth”) still dominates much of the countryside and regularly murders bigwigs and blows up hotels and restaurants in Mogadishu, the seaside capital that was once an Italian colonial jewel. Famine, terrorism, corruption and clan factionalism have prevailed. A swathe of Somalia’s people—2m out of 12m, some say—has fled abroad.

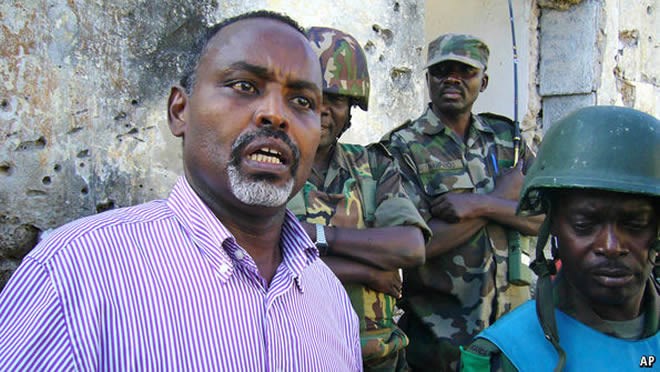

Amid this remorseless gloom, however, Andrew Harding, one of the BBC’s most intrepid and empathetic journalists, who has been visiting the country since 2000, has chronicled the extraordinarily uplifting life of one Somali, Mohamud Nur, nicknamed Tarzan. Dumped as a child in an orphanage in Mogadishu, he later made good in Saudi Arabia and then London, and returned to Somalia in 2010 to become the capital’s dynamic mayor. According to Mr Harding, Tarzan’s courage, inventiveness and resilience typify the finest qualities of the Somali people. It would be wrong, he insists, to give up hope.

Yet it is hard, despite the best efforts of Tarzan and his BBC booster, to be optimistic. Perhaps the biggest reason for despair is the Somali clan imbroglio, which has long been a recipe for internecine division. Mr Harding quotes an old Somali proverb:

Me and my clan against the world;

Me and my family against my clan;

Me and my brother against my family;

Me against my brother.

In Tarzan’s case, though he hails from a tiny sprig of one of the big four clans, he was endlessly tripped up by envious rivals, often stirred up by a sense of clannish competition. Somalis as a whole are homogenous, speaking the same language and sharing one religion and culture. Yet the extraordinarily intricate web of clans can lethally “divide and destroy”.

Another source of division, documented by Mr Harding through the prism of Tarzan’s family, is the resentment felt towards the scattered Somali diaspora, especially when its members return home (even though remittances are crucial to the survival of many of those who have stayed behind). Tarzan’s wife and six children were by no means thrilled to come back after two decades in London. Mr Harding poignantly describes the churning of emotions that many migrants (not just Somalis) experience as they are tossed and tugged between competing cultures. Tarzan’s wife Shamis talks of “being marooned between two identities”.

Though the violence that runs like a thread through every aspect of life in Mogadishu is usually attributed to al-Shabab, Mr Harding makes it clear that it is also endemic among those who are meant to be jointly opposed to the jihadists. Mogadishu, says Tarzan, is “a city of sharks”. Business rivals are liable to bump each other off—and blame al-Shabab.

Another twist, in this tangle of suspicion, is that the differences between al-Shabab and the beleaguered new establishment to which Tarzan belongs are often quite narrow. People change sides. Cousins, even brothers, fight on opposing sides. A close friend of Tarzan’s was killed by a cousin’s suicide-bombing daughter. His own cousin returned from America to join al-Shabab—and then switched sides again. “If you see him, if he comes close to my house, shoot him,” Tarzan told his guards. They were later reconciled, more or less.

After four topsy-turvy years Tarzan was bounced out of his job. His courage and dynamism were undisputed. But he also faced envy-driven charges of malfeasance and thuggishness, which the author, who clearly admires his subject, leaves studiously unanswered. Whereas Shamis apparently flits between a business in Dubai and her old home in north London, where most of the couple’s children still reside, Tarzan has hunkered down in Mogadishu, perhaps poised to bid for the presidency in the upcoming indirect election.

“Somalia has slowly begun to make measurable progress,” writes Mr Harding in a final, doggedly optimistic passage. “Piracy has almost stopped. Al-Shabab controls much less territory, there is oil offshore, a flourishing livestock industry, and a talented and wealthy diaspora. And yet the politics are still dangerously messy, fuelled by the greed of unaccountable politicians. This may no longer be a ‘failed state’, but the jigsaw is still in pieces.” You can say that again.

This article appeared in the Print Edition with the headline: Hope among the horror