Saturday February 20, 2016

By Ibrahim Hirsi

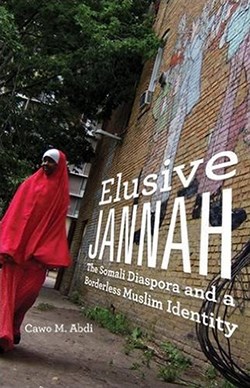

University of Minnesota Professor Cawo Abdi’s new book, “Elusive Jannah,” explores the experience of Somali immigrants in the U.S., South Africa and the United Arab Emirates.

Long before they flooded into many parts of North America and Europe, Somalis romanticized another part of the world: Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, regarding the region as dream destination. In the 1970s and 1980s, Somali men often journeyed to the oil-rich nations in the Middle East in search of jobs — and with the goal of sending financial assistance to those left behind, building houses for loved ones and buying cars in a country where only a few privileged people drove.

The income these workers generated in the region earned them a symbolic status among their peers in the East African Somalia, which struggled with chronic unemployment under the authoritarian government of General Mohammed Siad Barre.“Often [these men] were marrying the most beautiful girls in old villages,” noted Professor Cawo Abdi of the University of Minnesota. “There was that sense that they went to a place that resembled Jannah.”

Jannah — the Arabic word for paradise — inspired the title of Abdi’s new “Elusive Jannah” book, which she will discuss during an event on Saturday afternoon at the Cedar Riverside People’s Center, near the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management.

The book details the identities, struggles, achievements and the lives of Somali immigrants in three very different countries: the United States, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

“What I’m basically comparing is the three settlements, three immigration policies and how they shape the migration experience of Somalis,” said Abdi. “In each place, Somalis find certain things that are positive, but also they experience certain challenges that are unique to the context.”

Elusive paradise

Some decades ago, many in Somalia imagined that everyone who sets foot in the Gulf region becomes wealthy by default — with no consideration of the kind of jobs those workers held.

“Those could have been the ones washing the bathrooms, driving trucks, doing basic unskilled work,” Abdi said of their jobs. “But because of the condition that they’re living in, they imagine that the other side has green pastures.”

Since the civil war erupted in Somalia amid the ousting of President Barre in 1991, though, the assumption that the Middle East had “roads paved with gold” has shifted dramatically, and people began looking to the United States for the sort of lifestyles they saw in Hollywood movies. This shift in thinking came as a result of the immigrants who began to pour into the U.S. through refugee resettlement and other humanitarian programs.

But it isn’t only Somalis clinging to the elusive paradise-like lifestyle of America, said Abdi. She noted that it’s typical for people in the developing nations to view the U.S. as “the most coveted migration destination” in the world — a place where everything is within arm’s reach.

“In the book, many said that they thought that they could make hundreds of millions of dollars within a short period of time,” Abdi said. “There’s a huge disconnect between the realities of migrants and refugees, and the way all migrants and refugees imagine the western destination.”

‘Reality sinks in’

Over the past two decades, tens of thousands of Somalis escaping the unrest in their country have made Minnesota their home. Often times, they come here after years in refugee camps in Kenya and Ethiopia.

In Minnesota, while some thrive economically, many struggle to make ends meet. A University of Southern California study noted last year that more than 55 percent of Somalis in the state live in poverty.

“They start at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder of the U.S. population,” Abdi explained. “And all of a sudden, almost within days and months, reality sinks in. That can create cultural shock in a sense. But also disillusionment, in terms of what they expected and what they encountered in everyday living reality.”

One of the first hurdles the new arrivals encounter in Minnesota, according to Abdi’s book, is a lack of employment around the metropolitan area. So, they venture out to the outskirts of the Twin Cities — including St. Cloud, Faribault and Marshal — in search of jobs at the meat processing and assembly plants.

Then, what they see in the workforce contradicts the generally held views of life in America, as Abdi writes in the book: “Somali male interviewees working in the meat processing plants dwelled on their initial disbelief at working in the meat industry, a sector that has negative clan connotations in Somalia. Minority clans who were looked down on and discriminated against in Somalia were associated with this type of work, though in reality poor people of all clans performed such jobs.

“The grueling physical toll meat processing plant work takes offered a particularly brutal contrast with refugees’ long-held dreams was possible in America.”

More than money

At a time when immigration topics remain one of the hottest in the news, the mainstream media and politicians often depict immigrants and refugees as if they all come here solely in pursuit of financial gain.

But in the “Elusive Jannah,” Abdi reveals that there are different factors contributing to the stream of immigrants and refugees coming into developed countries, including the United States, Canada, Europe and Australia.

But in the “Elusive Jannah,” Abdi reveals that there are different factors contributing to the stream of immigrants and refugees coming into developed countries, including the United States, Canada, Europe and Australia.

For example, the book details stories of Somalis in the UAE and South Africa who run successful businesses. Though they qualify for some sort of legal document to stay in these countries, Abdi explained, they feel isolated from the rest of the world. “In South Africa, you can get refugee status,” she noted. “But that does not protect you from harassment, from exploitation, from bribery and from violence.”

No matter what the circumstance, the UAE doesn’t extend refugee status, Abdi said. Everybody is a labor migrant, with a visa requiring renewal every two years.

“The lack of refugee status, the uncertainty of what tomorrow might bring, the lack of mobility makes it very hard for Somalis,” she said. “Socioeconomically, they’re doing well — they have their own ethnic economy.”

She added: “So, the reason that a lot of people are taking these high, high risks … is much more complex than only, ‘they want to go to Europe … and America to find better jobs and better lives.’ But it also leads to a decent, dignified life, which often is denied to a lot of refugees and migrants.”