Wednesday, December 14, 2016

By RHODA ODHIAMBO

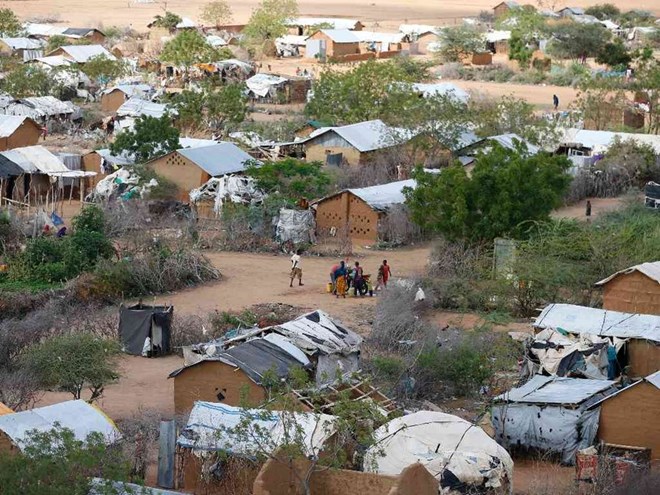

A part view of the IFO 2 Refugee camp in Dadaab on November 23, 2016. Several refugees born and bred in the camps are in a dilemma following the expatriation orders as they consider themselves stateless by virtue of her birth at the camp. Photo/Jack Owuor

During a walk throug the five camps in Dadaab, now five months away from closure, one finds boys playing soccer or ‘swimming’ in puddles of water, and girls playing hopscotch or skipping rope. Those not playing are helping their parents look for firewood in nearby bushes. Others are fetching water or collecting sand for repairing their homes.

However, among the children born in the camps, some have never gotten the opportunity to make friends. The people they call friends are their siblings and parents.

Such is the story of four-year-old Bahsan Mahdi Mohammed. She was found wrapped in damp clothes in a bush in Dagahley camp by boys playing football. The boys alerted the police and took the baby to the Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Hospital. She was just days old when the boys found her.

“I got to know about the baby since I was under the foster parent programme run by Save the Children. When I saw the child, I told them that I volunteered to care for her as my own,” Muhubo Hassan Hilolwe, 51, says.

Muhubo, a mother of six, fled from Somali in 2008 with her entire family. She says ever since she moved to the camp, life has been difficult, especially four years ago, when gunmen attacked her family, tortured her and murdered her mother in front of her.

She looks at where her mother was murdered as we carry out the interview.

“We had just come from the evening prayers with my family. My mother was playing with her grandchildren while I carried Mahdi, who was crying. It is at that point where the gunmen stormed in and killed my mother before my family,” Muhubo recalls.

“Where is Muhubo? Where is Muhubo?” They asked her after shooting her mother four times. “I do not know where she is,” she responded.

“After I told them that, they hit me with a metal rod several times on my back, leaving me with two broken ribs.”

She says she tried to seek treatment at MSF, Dagahley, but the medics refused to attend to her.

“I wish I knew why they attacked my family and killed my mother. It might be because of Mahdi, my adopted child, or my income generating activity that I use to support my family. But they are the only ones who now why they did it,” Muhubo says.

“The attack left my children traumatised. They have nightmares every day and get paranoid during the day when someone knocks at the gate,” she adds.

Mahdi, on the other hand, seems to have forgotten about the ordeal, but she has a wound on her neck that she got from her neighbours.

Branded a 'bastard'

Wecel (bastard) they call her. That is the name given to orphaned children under the care of foster parents.

Muhubo says one of the neighbours scorched Mahdi with a metal rod to identify who among her grandchildren was adopted.

“She came back home writhing in pain. Mama! Mama!” she cried out. When her siblings told me what happened to her, I told her not to worry because it was wrong for the neighbours to hurt her.”

Muhubo tells me she has tried reporting the matter to the police station but the bloc leader told her he was going to sort out the matter. No action has been taken a year later.

Madhi does not know why she was assaulted and neither does she have any friends. She also has no idea that the family taking care of her is not her biological family. Her mother says she will not tell her she is not her biological mother because it will break her heart.

Her family’s compound is the only place she knows. She only goes outside if she is accompanied by her mother for fear of being ridiculed or being made to feel less of a child.

Children of mixed parentage

A few blocks from Muhubo’s house is Sadia Birka Jamari, 23. Sadia, an Ethiopian, is not a foster mother but is worried about her child’s safety.

She was in a mixed marriage with a Somali, who divorced her early this year, and is willing to go back home. She will be moved to Kakuma once the camp has been closed in May.

The two, who were married for a year, are currently engaged in a tug-of-war over who should keep the baby. Her ex-husband was unavailable for comment.

A census carried out by UNHCR and the government between July 4 and August 10 found that there are 283,558 refugees in Dadaab’s refugee camps.

Children alone account for 52.6 per cent of the population. Out of this percentage, 30 per cent are categorised as vulnerable, meaning they either arrived at the camp un-accompanied or were separated from their biological parents when they fled from Somalia.

Save The Children Dadaab manager Caleb Odhiambo says the census also highlighted an issue officials have never talked about: couples in mixed marriages with children.

“When the government decided that it wanted to close the camp, people noticed that some refugees are going to find themselves in a stateless situation,” Caleb says.

Sadia’s child is a case in point. The father was born in Somalia, while she was born in Ethiopia. Their child, however, is stateless. He was born in the camp two years ago and that is the only place he calls home.

“As an organisation, we believe that every child belongs in a complete family. Separating the child from both parents is not a idea. One cannot also say that what has been done is in the best interest of the child,” Caleb says.

“When it comes to movements of couples in such marriages who have children, we would leave it to the family to decide. Yes, we have kids who are born on Kenyan soil, but the policies on registrations of such people is not something the government would consider,” Caleb says.

Local intergration

Caleb says in order to save the children from the emotional and psychological pain they will go through should they be separated from their families, the government should consider local integration.

This is a complex and gradual process with legal, economic, social and cultural dimensions. It imposes considerable demands on the individual and the society. In many cases, it begins with acquiring the nationality of the country of asylum.

“This is a durable solution but no one is talking about it. All we are doing is repatriating people to a country that is not yet stable,” Caleb says.

Data from UNHCR shows that a total of 69,811 refugees are willing to return home against 213,747, who feel safe at the camps. Some 19,312 people are in mixed marriages. Most of them are Somali refugees in a union with residents, followed by Somalis married to non-Somalis.

Caleb also says that since the May 6 announcement, they noticed increasing unwillingness of foster parents to keep orphaned children.

“Some said the presence of a fostered child in their house would delay their repatriation process. This is because of how long it would take to process the child’s papers,” Caleb says.

Muhubo says she would go back to Somalia with all her children including Mahdi, because un-accompanied and orphaned children need to be taken care of unconditionally.

Foster parents who haven’t told the children where they came from also risk losing each other’s trust, especially if someone else breaks the news to the child.

“These people live in a community where some people do not appreciate families who take care of such kids. The problems that will be faced by parents who feel that telling the kids the truth will hurt them is that someone will beat them to it, especially their neighbours.” Caleb says.

“The community already has derogatory names for children and the family taking care of them. Some of them feel that such acts of kindness do not auger well with their culture,” he adds.

Fears for futures

Caleb says Save the Children’s greatest fear is that the children’s ambitions would be dimmed in Somalia. They would have challenges in accessing healthcare, education, and no one will be able to guarantee them a good livelihood like what they are being offered in the camps.

“Officials from Jubaland were here a few weeks ago and they said they do not have enough room to house refugees because of the high number of IDPs in Somalia,” Caleb says.

“They also noted insufficient funds to take care of all them as the other reason why they do not want the refugees back in their country.“

As the sun sets in the camps, the refugees keep counting the days the camps to the camp’s closure. A place some of them have called home for more than 10 years, some of whom have never seen the country they are being repatriated to.