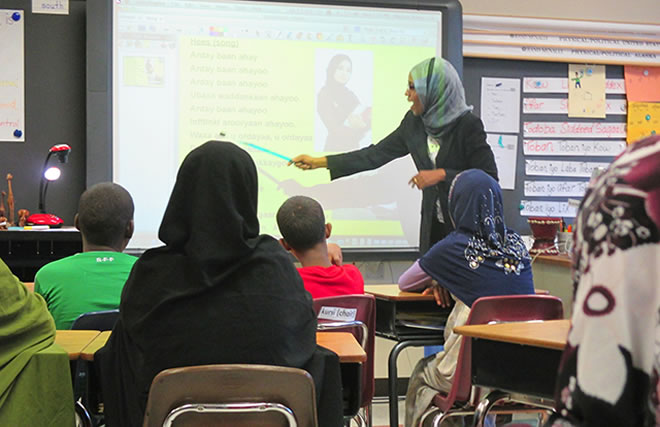

MinnPost photo by Beth Hawkins - Teacher Stephany Jallo reading the book "Wiil Waal" to the class.

By Beth Hawkins

Friday, October 11, 2013

A folk tale is a story that is passed on. One generation tells it to the next, which recounts it in turn to another. The process contains the germs of much: language, culture, identity, customs and relationships, among other things.As the human brain develops, folktales — as well as nursery rhymes, songs and other forms of word play — allow it to both categorize all of the aforementioned things and to relate them to one another.

Earlier this week Stephany Jallo and Miriam Adam took turns reading a folktale to a group of Somali children who have been in the United States, with one exception, for less than six months. The teachers read the story, “Wiil Waal,” in English and Somali, respectively.

The multi-grade class is one of two at Minneapolis’ Anne Sullivan Community School that make up NABAD, a brand-new pilot program designed to give refugee youth who have no experience of school a fighting chance at making up lost years. The name is both an acronym and a Somali greeting meaning “peace.”

Not only don’t these 20 middle schoolers speak much English, they have no experience reading or doing math in their native language and no exposure to the school-related concepts, like eating in a cafeteria or transitioning from one activity to another, that most kids learn in kindergarten.

A shepherd in long-ago East Africa, Wiil Waal, whose only riches are his many children, must decide which portion of a slaughtered sheep he should present to the sultan. His neighbors are giving the choicest cuts, but it pains Wiil Waal that his children will go hungry while the wealthy leader feasts.

Jallo, a veteran ESL teacher, and Adam, a Somali teacher who moved here from Ohio to take this job, are moving around the room, gesturing at body parts and pantomiming verbs as they move, seamlessly, from one language to another. By the end of the book, Wiil Waal’s oldest daughter has helped him resolve his dilemma.

The folktale was preceded by two other activities in which the concept of helping with central: A song in English that showcases helping verbs, and the recitation of a Somali text about being a student and helping your family.

Learning to navigate

“These students, they’re like that daughter” in Wiil Waal, explained Lynn Harper, the K-8 program facilitator for the Multilingual Department at Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS). “They’re helping their families learn to navigate things here.

Connecting their new skills and language to their prior knowledge will accelerate the process. If the program is a success, the intensified development will enable these students to enter mainstream sixth-, seventh- and eighth-grade classrooms next year.

“Here we have these great language-learning machines and they’re hit with all these new things,” said Harper. “We need to give them a way to characterize all of that information.”

The idea for NABAD sprang up in two places at once. Like other school districts, MPS has long struggled to accommodate waves of arriving refugees.

Typically immigrants and students still learning English are given English as a Second Language (ESL) services, bridging the transition from learning academic skills in their native language to learning in English.

Yet even when delivered in large doses by the most talented teachers, ESL doesn’t make up for the gaps present when an older child has never been to school. Concepts like long division or photosynthesis are hard even when you understand the words in which the lesson is being delivered, said James Kindle, the teacher in NABAD’s second classroom, which houses grades 3-6.

“There’s only so much you can do without losing the rest of the class so you can focus on the newcomers,” he said. Frustrations mount for student and teachers alike when students aren’t equipped to do things like wait in line for lunch or focus their attention on the lesson.

An ESL teacher at Sullivan, Kindle was one of several teachers who approached administrators about trying to meet the needs of this population in a different way. “Unbeknownst to me, the district was looking, too,” he said. “It just became, ‘How do we make this happen?’”

The “how” turns out to be a blend of creativity and persistence. Somali immigrant Adam was hired with an eye to staffing the pilot program, but her time is allotted to several classrooms. Jallo and Kindle get 45 precious minutes a day to co-teach with her.

The rest of the time they use a mix of tactics. Kindle uses the district’s multilingual help line — a service MPS contracted for relatively recently — for all kinds of translation assistance. Sometimes, he calls from his classroom phone and puts the translator on the overhead speakers.

Uses translators

He uses the translators — and their cross-cultural knowledge — to make calls home to parents to find out how things are done at home. He calls on them or on Somali support staff working at Sullivan to help him record bilingual lessons on an iPad that students can view before engaging in a “flipped” classroom activity.

He’s working on his own Somali, and he’s established very consistent, specific routines and rituals to minimize potential “hot spots” that eat up time. And he has support in math from another Somali speaking teacher.

The team — which has the enthusiastic support of Harper and Sullivan’s principal — is paying close attention to what does and doesn’t work. And they are emphasizing the skills that they believe will help kids start out next year in regular classrooms, still behind but equipped to catch up.

MinnPost photo by Beth Hawkins - Somali co-teacher Miriam Adam moved to Minnesota from Ohio to take this job.

“In one year you can’t get all the way up to speed,” said Kindle. “But you can get the most useful basics to get there.”

The progress needed is typically made over the course of several school years. For instance, Jallo started the bilingual segment of her day with a multi-faceted lesson that involved the short, simple sight words kids often learn in first grade — or in preschool, in middle- and upper-class families.

As she displayed “cat,” “fan” and “pan” on the board at the front of the room, Jallo asked questions about the words. Were they nouns? Can you hold them? What are they used for?

The group faltered when put up the word “cake” and asked whether anyone had a kind of cake for breakfast over the weekend. After several said eggs, the teacher put the word “pan” back up.

Hands shot up. “Oil,” several students supplied.

“Sambusa,” said another, meaning a Somali turnover, not unlike an Indian samosa, fried in oil in a pan.

Working through the question

As the class worked through the question, both Jallo and Adam repeated the sight words over and over, in anecdotes about their own families and stories about school.

By the time the group was nearing Wiil Waal’s resolution, two girls had their heads on their desks. As she circulated through the room with her copy of the book in one hand, Jallo stopped to feel the forehead of one and then the cheek of the other. Both girls sat back up.

The shepherd’s daughter told her father not to give the sultan the sheep’s rib — both teachers reflexively touch their own ribs — but the gullet. Standing in line with the inedible tissue in his hand and watching the best parts of the fattest sheep piled before the sultan, Wiil Waal trembles.

The sultan, however, beams. His gift is the most valuable. The gullet is the way to deliver shared food to the stomach. And sharing, he explains to Wiil Waal, allows people to live in peace.