Monday, May 14, 2012

By Craig Whitlock

advertisements

KAKOLA, Uganda — The heart of the Obama administration’s strategy for fighting al-Qaeda militants in Somalia can be found next to a cow pasture here, a thousand miles from the front lines.Under the gaze of American instructors, gangly Ugandan recruits are taught to carry rifles, dodge roadside bombs and avoid shooting each other by accident. In one obstacle course dubbed “Little Mogadishu,” the Ugandans learn the basics of urban warfare as they patrol a mock city block of tumble-down buildings and rusty shipping containers designed to resemble the battered and dangerous Somali capital.

“Death is Here! No One Leaves,” warns the fake graffiti, which, a little oddly, is spray-painted in English instead of Somali. “GUNS $ BOOMS,” reads another menacing tag.

Despite the warnings, the number of recruits graduating from this boot camp — built with U.S. taxpayer money and staffed by State Department contractors — has increased in recent months. The current class of 3,500 Ugandan soldiers, the biggest since the camp opened five years ago, is preparing to deploy to Somalia to join a growing international force composed entirely of African troops but largely financed by Washington.

After two decades of failed efforts, the U.S. government and its allies in East Africa say the interventionist strategy is slowly bolstering security in war-torn and famine-stricken Somalia, long considered the most ungovernable country in the world.

Ever since it plunged into chaos in the 1990s, Somalia has destabilized the region, serving as a hub for Islamic extremists and bands of pirates who plunder some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. American officials have long worried that al-Qaeda leaders will seek to rebuild their global operations in Somalia and nearby Yemen, across the narrow Gulf of Aden.

A mock urban setting nicknamed “Little Mogadishu” includes threatening graffiti, such as, “Death is Here! No One Leaves,” to immerse the peacekeepers into the combat experience. Washington is relying on proxy forces because Somalia has been essentially off-limits to U.S. ground troops since 1993, when Somali fighters shot down two military helicopters and killed 18 Americans in the "Black Hawk Down" debacle.

Ben Curtis / AP

Since the fall, however, these troops have chased al-Shabab, the Somali militia affiliated with al-Qaeda, out of Mogadishu and solidified control of the capital. In February, the African Union announced plans to expand the size of the force from 12,000 to 18,000, and is preparing to deploy troops to southern and central Somalia for the first time.

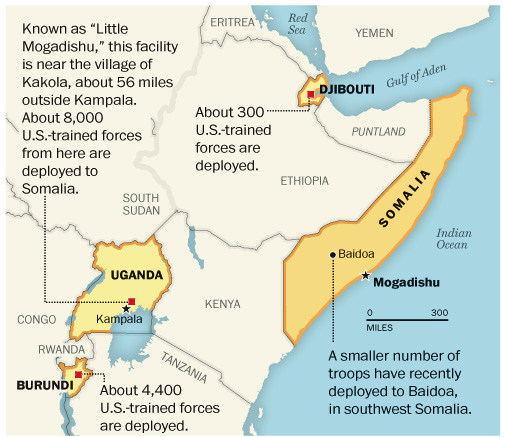

About three-quarters of the force — mostly Ugandans, but also soldiers from Burundi, Djibouti and Sierra Leone — will have been trained by U.S. contractors hired by the State Department. U.S. military trainers are playing a supporting role, offering specialized instruction in combat medicine and bomb detection, among other subjects.

“At the end of the day, if you look at all of this and say, ‘Is it worth it?’ ” said Army Lt. Col. Luis Perozo, the defense attache at the U.S. Embassy in Kampala, Uganda, “and I would say, all you need to do is look at what’s going on in Mogadishu.”

The boot camp here, known as the Singo Training School, is operated by the Ugandan military, but the instruction is overseen by MPRI Inc., a subsidiary of L-3 Communications, based in Southeast Washington. It is one of four State Department contractors that are training African troops for Somalia.

Between one dozen and two dozen MPRI instructors are posted to the Singo camp at any given time to run the 10-week training course. All are veterans of the U.S. Army or Marine Corps, and most served in Iraq or Afghanistan, U.S. officials said.

The State Department and Ugandan military allowed a handful of journalists to visit the camp recently but declined to permit MPRI trainers to speak on the record.

Since 2007, the U.S. government has contributed about $550 million to train, equip and subsidize the African Union troops in Somalia. The European Union and United Nations are the other major donors.

Washington is relying on proxy forces because Somalia has been essentially off-limits to U.S. ground troops since 1993, when Somali fighters shot down two military helicopters and killed 18 Americans in the “Black Hawk Down” debacle.

U.S. Marine Sgt. Albert Winschel, right, demonstrates the use of an improvised tourniquet on fellow Marine Sgt. Preston Norton, as they instruct soldiers from the Ugandan army in medic training.

Ben Curtis / AP

Thanks to an influx of U.S. aid and equipment, the Ugandan military has been willing to step into the breach. Ugandan officials have pledged to increase their forces in Somalia to 8,000 troops, the largest foreign contingent (Kenya and Burundi are the other major players, each contributing about 4,500 troops).

U.S. officials praised the Ugandans’ performance and military skills.

“They’re a very professional army,” said Maj. Albert Conley, deputy chief of the office of security cooperation for the U.S. military in Uganda. “I’ve never had a discussion on Clausewitzian theory with an African military officer before, but I have here.”

Ugandan military officials said they have had no trouble finding recruits willing to go to Somalia, despite the dangers. “It has stepped up our credibility in the region, and any soldier would be very proud to be part of the mission,” said Col. J.B. Ruhesi, the Ugandan commander of the Singo training camp.

Financial incentives also play a major role. The African Union pays troops about $1,000 a month to serve in Somalia — quintuple the usual salaries for many enlisted Ugandan soldiers.

Ugandan military officials said about 80 of their troops have been killed in Somalia since 2007, although analysts suspect the number of casualties has been far higher.

A leading cause of death for the African Union troops in Somalia has been homemade bombs — al-Shabab’s weapon of choice. U.S. trainers said they recently upgraded their course of instruction to help recruits learn how to avoid the explosives.

To that end, the Defense Department recently sent about 20 Marines to the Singo training camp to provide specialized instruction in combat medicine and bomb detection. Although the Marines have never fought in Somalia, they have years of experience dealing with homemade bombs in Iraq and Afghanistan

“When it comes to IEDs, there’s really nothing new under the sun,” said Marine Staff Sgt. Neal Fischer, referring to improvised explosive devices, the military’s term for rudimentary bombs.

Fischer acknowledged that many of the Ugandan recruits are “raw” but said they were fast learners. “We’re looking to enhance their mobility in the field,” he said. “They’re here to learn this skill set so they can go back to Somalia.”

Ugandan military officials said about 80 of their troops have been killed Somalia since 2007, although analysts suspect the number of casualties has been far higher. Ugandan military officials said they have had no trouble finding recruits willing to go to Somalia, despite the dangers. “It has stepped up our credibility in the region, and any soldier would be very proud to be part of the mission,” said Col. J.B. Ruhesi, the Ugandan commander of the Singo training camp.

Ben Curtis / AP