By HIBAH ANSARI

Tuesday March 2, 2021

As a teenager, Zaynab Abdi got a visa to move to the United States. Her younger sister Sabreen didn’t. The Trump ‘Muslim ban’ has kept them apart for seven years.

Zaynab Abdi, 25, came to the United States in 2014. Now, she's trying to reunite with her sister after seven years. Credit: Jaida Grey Eagle | Sahan Journal

After graduating high school, Zaynab Abdi joined a Twin Cities soccer team. The club brought her a great opportunity: the chance to represent the United States in a 2017 tournament. But the invitation also raised a problem: The tournament was in Norway.

“Being a green card holder and being ‘double-banned’ from Somalia and Yemen, I wouldn’t be able to come back,” Zaynab said. “So, I had to cancel. My coach was so mad.”

Zaynab, 25, wasn’t exaggerating when she said she was “double-banned.” In 2014, she immigrated to the United States from Yemen, where she’d landed as a refugee from Somalia in the 1990s. Travelers from Somalia and Yemen couldn’t enter the United States under the terms of former President Donald Trump’s travel ban. The ban didn’t just keep Zaynab from playing in a soccer tournament, though. It separated Zaynab from her younger sister, Sabreen, for almost seven years.

In a symbolic move on the first day of his administration, President Joe Biden lifted the ban. Now, Zaynab is making plans to see her sister. But fear and insecurity about her own immigration status have put that on hold. And immigration experts say sweeping change will be necessary for families like Zaynab’s to reunite.

Widely known as the “Muslim ban,” the executive order Trump signed during his first month in offiice banned travel from Muslim-majority countries like Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. After the haphazard rollout, lawyers and protesters flocked to airports to help figure out what the ban meant for friends and family members trying to come home from the banned countries.

Eventually, legal challenges led to a few countries falling off the list. But two countries—Somalia and Yemen—remained off limits.

Zaynab has lived through a civil war, two political revolutions, and a Trump presidency that felt relentlessly hostile to Muslims. In response, in the seven years she’s lived in the United States, Zaynab has taken an active role in civic engagement—even though she couldn’t vote.

From Somalia to Yemen to Egypt—without a parent

Zaynab had arrived in the United States just a couple of years before Trump started to hype up his voter base with bluster about banning Muslims from the country. But Zaynab had experienced this type of disruption in the U.S. immigration system before.

The Abdis left Somalia during the civil war and fled to Yemen in the 1990s. Zaynab said she didn’t grow up with her father. Soon after the family came to Yemen, Zaynab’s mom received a diversity immigrant visa, also known as a lottery visa, to come to the United States. So she left, with the hope she could become a U.S. citizen, and eventually sponsor the rest of her family to join her.

Their journey turned out to be much more complicated.

“It felt like a happy journey— I’m going to be in a safe country, I’m going to have better education, I’m going to see my mom. But at the same time, I left my home, I left my people, my neighbors—my sister.”- ZAYNAB ABDI

Zaynab’s mother remarried in the United States and had two more daughters. Her grandmother raised Zaynab and Sabreen in Yemen. But in 2010, she passed away. A few months after her death, the Arab Spring hit the region, and a political revolution made the country unsafe for Zaynab and her sister. In 2012, they fled to Egypt with other extended family members and neighbors.

The loss of her grandmother and living in a new country weighed on Zaynab, who was just 16. She’d kept in touch with her mother on her grandmother’s cell phone—and now that was gone, too. In Egypt, she bought her first phone and could finally communicate with her mother again.

Though Egypt is another Arabic-speaking country, the environment felt completely unfamiliar.

“It feels like you’ve left the Earth to a different planet,” Zaynab said.

And then, a revolution—a second revolution—erupted in Egypt. At this point, Zaynab and her sister applied for visas to the United States. About a year later, they both attended interviews for the application process.

Zaynab got her visa; Sabreen didn’t. Seven years later, they still don’t know why the U.S. rejected Sabreen’s application.

“It felt like a happy journey: I’m going to be in a safe country, I’m going to have better education, I’m going to see my mom,” Zaynab said. “But at the same time, I left my home, I left my people, my neighbors—my sister.”

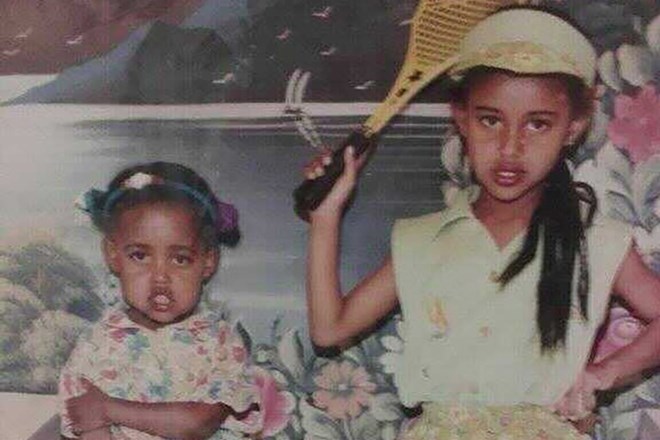

Zaynab Abdi and her sister Sabreen grew up together in Yemen and Egypt. Credit: Zaynab Abdi

Family separation—and plummeting visa numbers

Veena Iyer, executive director of the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota, said the organization has worked on a variety of immigration cases that have run into the travel ban in different ways.

“The biggest impacts that we have seen from the travel ban are the separation of so many families,” Iyer said. “The travel ban had discriminatorily said that folks who are from certain countries couldn’t reunite with their family members here.”

Iyer noted that some people were in the midst of the visa process when the ban went into effect. Their lives have been stalled ever since.

Regardless of their immigration status, people from the selected countries were scared to travel outside the United States, Iyer said. People who were abroad had concerns about what might happen at customs when they returned to an American airport.

Iyer said the decision to come back to the United States became even more difficult when the Trump administration expanded the ban in February 2020 to include six more countries: Nigeria, Eritrea, Tanzania, Sudan, Kyrgyzstan and Myanmar.

That disruption rapidly showed up in the number of visas the United States issued after the travel ban went into effect. According to the State Department, the United States granted 1,797 visas in 2016 to immigrants from Somalia. In 2019, a year after the ban went into effect, the United States issued only 464 visas.

From Yemen, 12,998 immigrants received visas in 2016, compared to 4,379 in 2019.

That data doesn’t include refugees and asylum seekers who encountered their own Trump immigration restrictions. In the past four years, Trump set a record low for refugee admissions. In October, on his way out of office, Trump set the cap at a historic low of 15,000, a limit that will remain in effect for the next eight months.

Refugees from Somalia make up the highest number of arrivals in Minnesota, with over 13,000 refugees in the last 15 years, according to the state’s Department of Human Services. A growing number of refugees from Myanmar have also relocated to Minnesota. Both countries landed on the travel ban list.

Since receiving an American visa in 2014 and moving to the United State, Zaynab has continued to experience this immigration turmoil. While Zaynab attended Wellstone International High School, her sister’s visa application didn’t seem to be going anywhere. Zaynab formed a plan: In the next five years, she would pursue citizenship and then sponsor her sister.

Over the next couple of years, Zaynab graduated high school while her sister got married and had a baby. Neither of them were able to celebrate these moments together.

‘Why should I be silent?’

When she lived in Yemen, Zaynab wanted to be an architect. She had lived through two political revolutions during the Arab Spring. She couldn’t be bothered with American politics, Zaynab joked. That all changed when she started college at St. Catherine University in 2016 and needed to pick a major.

“I just wanted to lead a simple life,” Zaynab said. “When Trump was elected, that’s the moment it hit me—and it hit me strongly. Why should I be silent?”

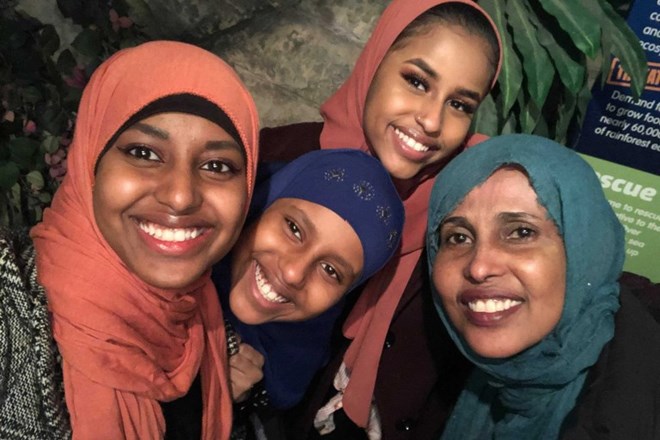

When Zaynab Abdi reunited with her mother after 15 years, she also got to meet two more younger sisters for the first time. Credit: Zaynab Abdi

Despite the fact that Zaynab wasn’t a citizen, and therefore couldn’t vote, she found ways to get involved. She’d done a bit of voter education in high school. Now, in college, she told her story to people of all ages, so that they could understand how Trump’s campaign promises would affect immigrant families.

She quickly shifted her interest from architecture to her new majors: political science, international studies, and philosophy.

Zaynab noticed that most of the civic engagement initiatives at St. Catherine’s involved getting out the vote and organizing debate watch parties. As someone who was learning about a new system of government herself, she said she wanted to make sure students and staff also had the information they needed.

She received a grant from the student senate to organize events and became the student coordinator for civic engagement. Zaynab became the university’s first Newman Civic Fellow, in 2019. Fellows are nominated by the school’s president based on their potential for public leadership.

When Zaynab graduated college in 2020, she felt well prepared to take on her first job: civic engagement coordinator for Reviving the Islamic Sisterhood for Empowerment (RISE). RISE is a Minneapolis-based nonprofit group of Muslim women that aims to amplify the voices of its members.

The 2020 election was just a few months away. “It was so beautiful,” Zaynab said of the work she did phone banking and educating voters. “Even though most people thought Trump will win again, you have that slight hope your hard work in the past four years isn’t going to go away.”

Nausheena Hussain, the executive director of RISE, recognized that their group could not singlehandedly reverse the Muslim ban. But they decided to bring the stories of its members to the state legislature and the community.

“We understand that public perception influences public policy,” Hussain said. “We needed to really kick it into gear with Muslim women, specifically.”

Since 9/11, Hussain has seen anti-Muslim rhetoric hurt her community: Often the media and polticians have created false and overblown connections between Muslims and terrorism. Looking at that bogus narrative, Hussain said she’s not surprised that something like a “Muslim ban” would resonate with some Americans.

“It’s such a difficult brand that we have on us now,” Hussain said. “Most of the things that are happening in the Middle East and Arab nations—the victims are Muslims.”

Despite only living in Minnesota for about seven years, Zaynab brings an energy to RISE that shows her strong commitment to the community, Hussain said.

Hussain noticed that the Cedar–Riverside neighborhood wasn’t receiving much support earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, so she turned to Zaynab.

“She became besties with Hennepin County,” Hussain joked. Zaynab received masks and large bottles of hand sanitizer from the county. She dropped some off at mosques. And then she went to Karmel Mall, the Somali shopping center in south Minneapolis, and passed out hand sanitizers at stores. She stood at the mall for hours to distribute masks to anyone who wasn’t wearing one.

Rebuilding trust in the U.S. immigration system

During Biden’s campaign, Zaynab said she hoped his promise to lift the travel ban wasn’t “just sparkly flowers,” and that he would actually follow through. So when he signed an executive order reversing Trump’s travel ban on his first day in office, Zaynab felt excited.

Iyer, from the Immigrant Law Center, said she looks forward to the possibility of reuniting families. There are still a lot of cases backlogged, though. Iyer urged the current administration to make a real reinvestment in resources to address the backlog so that more visas can be processed.

Iyer added that an announcement isn’t enough. Immigrants will feel more comfortable with the process if they actually see more people receiving visas and reuniting with their families. “It’s going to take time to rebuild trust that, unfortunately, was destroyed in the last administration,” she said.

Zaynab isn’t taking any risks. She remains worried about how leaving the country could affect her immigration status. She said she would rather wait a year or so to become a citizen before reuniting with her sister, who now lives in Belgium. After seven years apart, she’s not sure what that will look like.

Zaynab gets to see her two-year-old nephew over FaceTime. She’s thought about trying to sponsor her sister’s whole family—but that presents its own set of challenges. Ultimately, Zaynab said she’s trying to come up with a solution that would minimize the family’s loss.

“I think of it as a cake,” Zaynab said of all the major moments in her life.

When she was separated from her mom, one of the pieces of cake was gone. When her grandma died, she lost another piece. When Zaynab came to the United States, she got her mom back and met two new sisters—but with Sabreen living far away, there’s still an empty plate at the table.