Saturday October 28, 2017

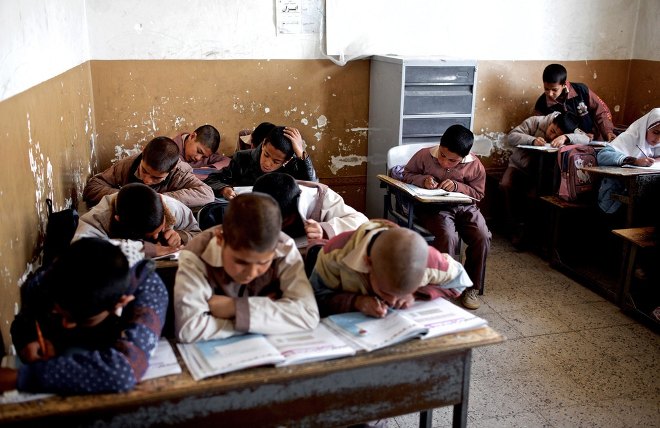

Afghan students attend a class at the Shahid Nasseri refugee camp in Taraz Nahid village near the city of Saveh, southwest of the capital Tehran, on Feb. 8, 2015. Photo: Behrouz Mehri/AFP/Getty Images

WHEN ABU FAZEL listens to news of the civil war still raging in Syria, he thinks about how he very nearly ended up a foot soldier there. But Abu Fazel isn’t Syrian, nor was he ever a would-be Islamic State fighter. He’s an 18-year-old Afghan refugee, living in the small city of Leverkusen, Germany. He spent most of his life in Iran but fled to Germany, rather than be sent to Syria by the Iranian government to fight on the side of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad.

Abu Fazel is one of an unknown number of Afghan teenagers that have been recruited by Iran to fight in Syria’s civil war over the past several years. Earlier this month, Human Rights Watch reported that it had identified the graves of eight Afghan children who had died in Syria, and collected evidence of other teenage recruits, some as young as 14. Conscripting children under the age of 15 as soldiers in active hostilities is a war crime, Human Rights Watch noted.

Abu Fazel was 15 years old when he was set to begin training for Syria. He and Ali, another 18-year-old Afghan refugee living in Germany, told The Intercept about Iranian militias targeting teenagers in immigrant neighborhoods.

“We are cheap cannon fodder for them,” said Ali, which is a pseudonym. The Intercept is also referring to Abu Fazel by only his first name because both youths fear retaliation against their families still living in Iran.

There are an estimated 3 million Afghan refugees in Iran, most of whom get by on black-market jobs and face racism and abuse, as well as scrutiny from the Iranian government. Afghan children often can’t attend school. “Afghan,” Abu Fazel said, is a common slur in Iran, and one he heard too often. “We were second-class citizens,” he said.

Vulnerable Afghan refugees have been prime targets for the Iranian government looking for military manpower in its alliance with Assad, as years of fighting have taken a toll on Iran’s own paramilitary units, like the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-controlled Basij militia. Although Assad’s Ba’athist government is nominally secular, Iran has used its self-image as the main representative of Shia Muslims worldwide to frame the conflict as a religious war against Sunni extremists. Many Afghans in Iran are Shia Hazara, a minority group in Afghanistan, and thousands of them have been sent to fight with other Shia fighters from Iraq or Pakistan. Other Afghans were drawn to sign up by the promise of a few hundred dollars a month or obtaining legal immigration status in Iran.

Ahmad Shuja, an independent analyst and researcher in Kabul, said that some fighters have been recruited directly from Afghanistan.

“Fighting in Syria has created pull factors for poor and undocumented Afghans in Iran, as well as poor Afghans in Afghanistan who face increasing sectarian persecution,” said Shuja.

“An undetermined but significant number of those Afghans fighting in Syria are children. We see their photos in propaganda materials,” he added. “We also see their funeral announcements.”

ABU FAZEL TOLD The Intercept that members of both the IRGC and the Basij regularly visited his predominantly Afghan neighborhood in Tehran. Abu Fazel and Ali both said that, ironically, the war had in some ways improved conditions for Afghans in Iran, because the government has allowed more Afghan children to attend state schools with mixed classes and given out more residency permits as part of outreach to the communities.

“They met young men in mosques and persuaded them to fight against ISIS or Al Qaeda,” Abu Fazel said. “They used to talk very softly to all of us. Many people, including myself, didn’t even realize that we were trapped in their propaganda.”

Other Afghan teenagers and family members told Human Rights Watch that soldiers were supposed to be 18, but recruiters did not ask for proof of age. Some families said their children had lied about their birthdates in order to sign up.

The recruiters had managed to persuade Abu Fazel’s cousin, who was also a teenager at the time, to join the fighting in Syria. The cousin had become a member of the Liwa Fatemiyoun, an Afghan division whose alleged main purpose is the defense of the shrine of Zaynab, the Prophet Muhammad’s granddaughter, in southern Damascus. (Iranian state media has stated that there are about 20,000 Afghans fighting in the division.)

Eventually, in 2014, Abu Fazel decided to go to Syria as well. Then, that August, his cousin was killed while fighting Syrian rebels near Aleppo. Abu Fazel saw that the Iranian newspapers described him as a “martyr,” but one week before his own three-month-long training was supposed to start, Abu Fazel decided to flee.

“I came to the conclusion that I cannot live as a killer,” he said. He had lost his father to the Afghan civil war in the 1990s and said that he “started to believe that even the worst ISIS or Al Qaeda member might have children who love their father.”

Abu Fazel feared that he would be deported because he had refused to fight and so, together with other Afghan refugees, he left Iran. After a harsh trip across a well-trod refugee trail leading through Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans, he finally reached Germany, where he asked for asylum based on the fact that Iran tried to send him to Syria. (His first application was rejected, but he is still waiting for a second petition to be resolved.)

Eighteen-year-old Ali also fled Iran for Germany for fear of being pressured into going to Syria. Many of his friends had gone and never returned, he told The Intercept. Ali’s family, who is Hazara from the northeastern Afghan province of Ghor, fled the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan for the Iranian city of Mashhad in the 1980s, and now they have been dragged into another war.

According to Ali, his father went to Tehran in July 2015 to try to find a way to get legal residency for the family.

“The authorities told him that fighting in Syria might be a possibility to get residence permits and other documents for all of us. Otherwise we all would be deported to Afghanistan very soon,” Ali said. His father and uncle have now been in Syria for over a year, however, and none of his family members have received legal status from Iranian authorities.

“This was just a trap to lure more Afghans,” said Ali.

Ali has lost contact with his father, but he still receives pictures and videos via WhatsApp from his uncle, who is deployed in Aleppo with other militia groups. Ali thinks that few Afghans believe that fighting in Syria on the side of Assad is “a good thing.” The majority of them are trapped in an exploitative situation. “Most of them want to ensure the future of their families, their wives, and children in Iran,” Ali said.

Ali Fathollah-Nejad, an Iran expert at Brookings Doha Center, said that “by deploying Afghans to fight its war in Syria, Iran effectively misuses the dire situation of Afghans inside its borders, millions of which have sought refuge in Iran from their war-torn home country.”

In a statement accompanying the group’s research, Sarah Leah Whitson, executive director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa Division, said, “Iran should immediately end the recruitment of child soldiers and bring back any Afghan children it has sent to fight in Syria.”