Friday, October 28, 2016

By Kate Morrissey

San Diego Unified School District has changed its program for immigrant middle school and high school students who don’t speak English in a way that the district says empowers the students but critics say sets them up to fail.

For almost a decade, such students — many of them refugees — spent their first year in a classroom with others like them in what the district called New Arrival Centers.

The students stayed with the same teacher most of the day, learning English and core subjects and joining other students for less academic classes such as physical education or art.

Starting this school year, the students are learning math, science and other core subjects in classrooms with native English-speaking students. A language “coach” accompanies the students to these classes to support them as well as their teachers.

The new program’s purpose is to recognize the value of the knowledge that the students arrive with, even if they cannot yet convey that knowledge in English, according to Sandra Cephas, the director of the district’s office of language acquisition.

The district was worried about isolation from the rest of the school, Cephas said.

“We don’t believe that just because they have a gap in language that they aren’t able to accomplish great things, because they can,” Cephas said. “That belief in them has to be coupled with the right support at the right time."

Cephas said the new program will accelerate the students’ language acquisition and provide equal access to the curriculum..

“The goal is for the entire school to embrace these students,” Cephas said.

She said the changes have not affected the school’s budget.

Teachers, parents and students have all expressed concern over the changes, especially for newly arrived students who had pauses in their education because they come from war-torn countries or refugee camps. Some have never been to school before and are not literate in their native languages.

Kris Larsen, who taught for the New Arrival Center at San Diego High School before retiring at the end of this past school year, said the teachers were not convinced that the changes were based on sound research.

“I get that they want to raise graduation rates,” Larsen said. “It’s absolutely absurd to think pulling these supports will raise graduation rates.”

Class size

The New Arrival Centers enabled the district to “significantly lower class size” for new arrivals and other English learners, according to Debra Dougherty, who worked in the office of language acquisition when the New Arrival Centers were created and also retired this past school year. She said it was one of the reasons the school was able to receive federal funding earmarked for immigrants and English learners.

This year, many of the classes that these students attend — now called “International Centers” — are at or near capacity. The effects of any crowding are somewhat eased because of language “coaches” added under the new program, putting more than one teacher in the classroom at a time.

On a recent Thursday, 36 students — the maximum allowed in one class for the district — surrounded three long tables in Lotus Hang’s English language development class at Mann Middle School.

According to the principal, Hang began as the Mandarin teacher before transitioning about five years ago to teaching English language development.

Posters with the names of colors, body parts and emotions lined the walls. The room filled with the hubbub of middle schoolers.

Nicole Rawson, language coach for the class, read the book “Malala: A Brave Girl from Pakistan” aloud. Students sat in pairs, sharing handouts. Hang projected a copy of the story on the overhead with notes written over some of the vocabulary, like the word “bully” scribbled over “Taliban fighter.”

A student teacher — there one day a week — moved among the students, making sure they were on the same page and whispering quietly with pairs of students.

Hang held up a sign that reminded the students to sit up and listen.

One student gave up on the reading and put his head on the table as students broke into pairs to discuss questions about what they’d read so far.

The students — sixth, seventh and eighth graders — spend half of the day with Rawson and Hang learning a combination of reading comprehension, language skills and the basics of how to go to school, like taking notes.

They then go to grade-level math and science, and either Hang or Rawson accompanies them for language support. They round out the day with an elective such as art.

“Even I was skeptical at first,” Rawson said. “It seems chaotic maybe, but it’s really controlled chaos, and the kids are thriving.”

The principal at Mann, Allen Teng, said he was born in Seattle, his first was language was Mandarin and he was educated as an English learner in elementary school.

“I sympathize with the challenges,” Teng said. “You have to catch up multiple years.”

He said he thinks the change comes from a good place, and that exposure to a variety of native English speakers in grade-level classes can help the students learn the language more quickly.

“We want to give them exposure to other language models, but at the same time we don’t want to put them in a place where they sink,” he said.

Parents respond

Those opposed to the changes have formed a Parent Student Resident Organization that meets at Mann Middle School to discuss issues for new arrivals at schools that feed into Crawford High, in City Heights.

According to Bill Oswald of the Global Action Resource Center, which focuses on refugees and civic engagement, one of the community’s main concerns is that the school district isn’t recognizing the difference between conversational English and academic English.

“The district is listening to their conversational English and saying they’re ready to go into a classroom, but research would say they’re not as ready as they seem,” Oswald said.

Cinthia Joselyne Vazquez, a former student of the New Arrival Center at San Diego High School, wrote a letter at the beginning of October about her experiences with the New Arrival Center. She recalled feeling lost and frustrated on her first day of school.

“The only thing that made me feel better was the fact that I was not alone,” Vazquez wrote. “I attended school 10 years in Mexico and getting used to the United States’ system was something almost impossible. I have always wondered what I would have done without the Newcomer program I was in and the answer always comes to be very simple — I would have dropped out of school.”

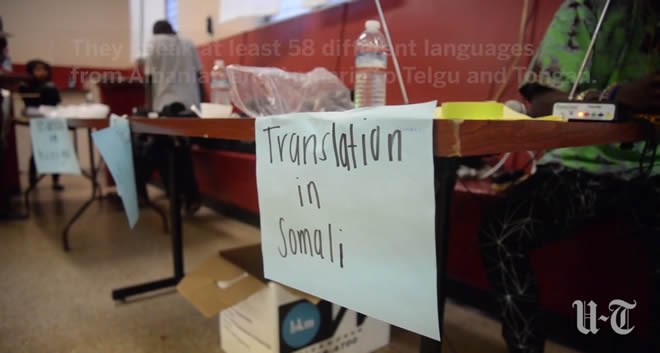

Mariam Ali, a Somali refugee who arrived in the U.S. in 1993, has been speaking on behalf of the area’s Somali families at the group’s meetings. She said she has 11 children, and five of them attend San Diego Unified schools.

“They took it away without discussing with parents,” she said of the New Arrival Center. “They just snatched it away.”

She said with the New Arrival Center, teachers were able to give students more one-on-one attention.

“Our children have never been to school,” Ali said. “They’ve never touched paper or pen in their lifetime. All they know is trauma, war, living in a refugee camp. We came here. Instead of getting help, we’re getting even more traumatized.”

She said she thinks schools in her area are not given the same resources as schools in areas like La Jolla or Scripps Ranch.

“They say there is no child left behind,” Ali said. “Our students are left behind. Immigrant students are left behind. Children of immigrants are left behind.”

The district has agreed to meet with representatives of the Parent Student Resident Organization in a committee that will decide the way forward for refugees.

In the district’s main planning document, it says the committee will “begin researching best and promising practices for working with Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE) and refugee students. The committee, composed of staff, parents, and students, will recommend a framework for addressing the unique academic, social, and emotional needs of SIFE and refugee students.”

Regulations and research

Under federal regulations, school districts have a lot of flexibility in how they run their programs for English learners as long as the program is based on research with proven results.

Local experts had different takes on the best approach for new arrivals.

Karen Cadiero-Kaplan, a professor in the department of dual language and English learner education at San Diego State University, said while she was not familiar with the specific program changes at San Diego Unified, most newcomer programs across the country focus first on language development and getting the students used to American school culture.

“They should have one year where they can get grounded into their new life in the country and school and then transition in with other English learners,” she said.

She also said limiting class size for newcomers to 20 or 25 students was ideal.

Gail Robinson, founding director of San Diego State University’s Language Acquisition Resource Center and author of the forthcoming book “Peaceful Conversations,” said she generally favored integrating the students with the rest of the school in addition to specialized English instruction and individualized help, though she was also unfamiliar with the specific changes in the district.

“Just because they lack certain skills in English doesn’t mean they lack skills across the board,” Robinson said.

Robinson said participating in mainstream classrooms meant the new arrivals would be able to learn from their English-speaking peers. She said the real challenge was to also develop practices that help the English-speaking peers learn from the new arrivals so that both groups feel valued.

Cephas, who designed the new program, said she had visited a program in Houston with a 98 percent graduation rate that helped guide the changes to the new arrival program.

“We are a strength-based system, giving students what they need when they need it,” Cephas said.

She said she also asked the county office of education and the California Department of Education for guidance in drafting the new program.

Cephas, whose family is from Tijuana, was also an English-learner at San Diego Unified in early elementary school. She said having a teacher that believed in her abilities made all the difference.

“I know they can do it. They have the ability to do it,” Cephas said. “I’ve seen it time and again.”