Plan to close the world’s largest camp is illogical and illegal – but scores much-needed political points, argues the Daily Maverick

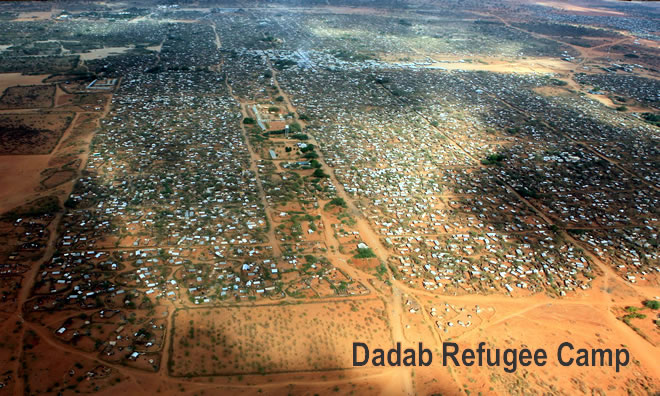

Newly arrived refugees at Dadaab, currently the biggest refugee complex in the world. Photograph: Dai Kurokawa/EPA

Simon Allison

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

The Kenyan government has announced that it will attempt to close all of the country’s refugee camps, a move that could displace an estimated 600,000 vulnerable people.

However, it’s no coincidence that just a week before the statement the Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta officially began campaigning ahead of elections scheduled for next year.

The two events are closely related. Like leaders all the world over – just look at Donald Trump’s fixation on Mexican immigrants, or how Europe’s far right is capitalising on the migrant crisis – Kenyatta and his advisers know that scapegoating refugees is an easy way to score political points with voters.

It helps too that the refugee problem is inextricably linked with another of Kenyatta’s favourite campaign themes: the ongoing war in Somalia, which has brought with it the threat of terrorist attacks on Kenyan soil.

“Under the circumstances, the government of the Republic of Kenya, having taken into consideration its national security interests, has decided that hosting of refugees has come to an end,” the government said last week, making this link explicit.

It’s clear that by threatening to shut down the refugee camps, Kenyatta wins twice: he can portray himself as tough on terror and tough on refugees. But threats are one thing. The reality of closing down these huge and well-established camps – now de facto cities – is something else entirely.

We’ve heard this threat from Kenyatta before, but despite the belligerent promises to send the refugees home, Dadaab and Kakuma, two of the biggest refugee camp complexes in the world, remain open.

Why? Because Kenya’s government cannot simply tell hundreds of thousands of people to return to the war, famine and/or extreme poverty from which they fled.

Forget the legality of such a move for a moment (although there is no doubt that Kenya’s stance is illegal under international law). Consider the logistics: how would Kenya go about transporting nearly 600,000 people into active war zones like Somalia without their co-operation? Who would pay for this operation? And what’s to stop refugees from coming straight back over the border (construction has only just begun on Kenya’s border wall with Somalia, another of Kenyatta’s poorly-conceived “solutions”).

Even as the government ramps up its anti-foreigner rhetoric, the population of the camps continues to grow. Kakuma, for example, is registering hundreds of new arrivals each week, many of whom are fleeing violence in South Sudan.

But if it can’t shut them out, the government can make life more difficult for the new arrivals. In the face of Kenyan hostility, the burden of dealing with these new arrivals now falls squarely on the international community.

In the same statement, the government acknowledged their “decision will have adverse effects on the lives of refugees and therefore the international community must collectively take responsibility on humanitarian needs that will arise out of this action.”

However an aid worker in Kakuma said that the announcement was made without any prior warning to the camp’s international partners, and that even officials belonging to the government’s own Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) were taken by surprise.

DRA employees have allegedly been told not to return to work, leaving their positions in the camp unfilled and international agencies expected to pick up the backlog.

In a statement, Doctors Without Borders warned that Kenya’s lack of co-operation and threatened closure would have devastating consequences. “The closure would risk some 330,000 Somali lives and have extreme humanitarian consequences, forcing people to return to a war-torn country with minimal access to vital medical and humanitarian assistance… MSF is urging the government to reconsider this call,” the organisation said.

As election season gets into full swing, it’s hard to imagine this plea falling on anything but deaf ears within the ruling party. Because while refugees can suffer like anyone else, they can’t vote, and that makes them little more than collateral damage as Kenya’s notoriously cynical electioneering gets under way.

A version of this article first appeared on The Daily Maverick