Deepmala Mahla

Wednesday December 7, 2016

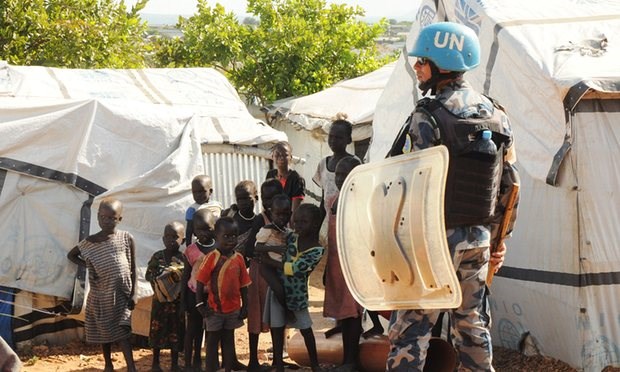

The number of South Sudanese needing food aid has doubled over the last year, rising to 4.8 million. Photograph: Reuters

In September, South Sudan joined a club where the fees are exorbitant and no one really wants to be a member. Along with Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia, it became one of the countries that has produced more than a million refugees.At Mercy Corps the way we view the world is to find opportunity in crisis. But, for the first time in my career, I am finding this tough. The people of South Sudan are resilient, but with the number of needing support to feed themselves and their families having doubled over the last year (now at 4.8 million) and most indicators of development on a downward spiral, it is difficult to identify the positives. And the truth is that although the war is at the heart of this crisis, short-term donor strategies and funding, crippling bureaucracy and a peace deal that the international community is holding on to, but which many South Sudanese have lost faith in, are all playing their part in making the situation worse.

No one is denying that conditions in South Sudan are gruelling. We work in a tense situation of ongoing conflict and violence trying to deliver aid to the most vulnerable. And while the fact that my team’s lives are on the line day in day out, is concerning to me as their country director, it is not what is keeping me awake at night. Our profession comes with certain risks, which we knowingly accept.

As aid workers we are trained to manage and implement programmes in times of conflict. We do this responsibly and sustainably, so that despite the fragility of the environment, we can move people along the road from relief to recovery.

But in South Sudan, we are not able to do this and it is this that grieves me. Just to begin with, we are suffering from diminished humanitarian capacity in the country, after the surge in violence in July, many humanitarian and institutional staff left and are yet to return. Moreover, while the NGO community perseveres in continuing to share best practice and recommendations for programmatic responses – both for urgent relief and medium term recovery – we are consulted only occasionally by donors on their strategies despite our rich on-the-ground experience and knowledge of what communities want and need.

For example, NGOs implement more than 70% of all programmes in South Sudan, but yet the main support from state actors is provided through pooled funding. What this means is that money is firstly put into a common pot, and from there it is donated to NGOs. This is not only an expensive way to operate, but it slows down implementation. Donating direct to NGOs would be more efficient, especially as there is no shadow of a doubt that the needs of South Sudanese people are exigent and cannot wait.

However, the most pressing concern affecting recovery is that the vast majority of our funding is received in short tranches: a couple of months, a couple of months and then another couple of months. What this means is that we are unable to plan long-term and nothing is guaranteed. We establish our programme, hire staff, implement for perhaps five months, and then wind down the programme again. We may (or may not) receive more funding for that programme, and so we start the cycle all over again. This is the reality in which we are working. We can do better.

In July, Mercy Corps with support from the British government began implementing a programme to stimulate economic recovery in some of the most inaccessible areas in Unity state.

This is a four-year programme, virtually unheard of in the recent times in South Sudan. We are providing cash transfers to households and traders to kick-start market recovery, as well as provide business training and livelihoods support for fishing and farming. It is precisely this type of programming that allows us to work sustainably in a manner that builds capacity and ultimately, enables the project to be taken over by the community. It is also more cost effective as we can plan efficiently, procure smarter, recruit better, and engage communities more meaningfully.

We cannot say that our programmes will not be interrupted by violence and conflict, but should this mean that we surrender all hope to help the South Sudanese people move forward beyond urgent relief and handouts? No. It means we adapt, we change our way of thinking and working. It means that donors become more flexible in their approach and understand that when there is an uptick in violence we will need to pivot from our recovery programmes to urgent relief, and then when we can, back again.

Around the world, Mercy Corps has implemented programmes with such nimbleness to shift between relief and recovery to fit the context, it requires trust, partnership, and commitment.

Without this change in approach, I will not be surprised if more international organisations leave South Sudan, or scale back their operations in the next six months. While we must have a peace deal that is firm, assuring and definite, that ensures the protection of civilians as well as aid workers, we also desperately need donors to reinvest and recommit to the future of South Sudan.