fiogf49gjkf0d

Continued from page 3...

By Erin Carlyle

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

|

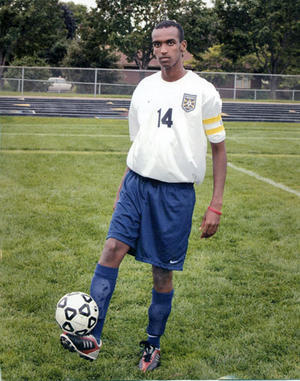

| Augsburg College student Ahmednur Ali aspired to become president of Somalia one day, but instead his life was cut short. He was murdered after volunteering at Brian Coyle Community Center. |

Abdishakur fell to the ground, dead. He was the sixth victim of Somali-on-Somali murder in the past two years, and the fifth in less than a year. "It's really sad," says Abdi, the documenatry filmmaker. "You just feel angry but you don't know who to blame. You are just hopeless. That's the worst thing that can happen to anybody."

FOUR DAYS AFTER Abdishakur was gunned down at the Somali mall, some 50 Somali students gathered to protest the gang violence that plagued their community.

"What do we want? Peace!" they chanted. "When do want it? Now!"

Their voices echoed past an internet cafe, around the corner to a barber shop, past great racks of colorful garments lined up against the shopping center's goldenrod-colored walls.

"Stop the violence!" they cried. "Somalis unite!"

Aman Obsiye, a soft-spoken, baby-faced former rapper from Dallas who cites Malcolm X among his heroes, captivated the crowd with his denouncement of local gang culture. Obsiye, 25, and four other young Somalis have founded a nonprofit focused on eliminating Somali youth violence. "If you look at the evolution of Somali gangs," Obsiye told the crowd, "we went from defending the community to destroying the community. Jumping, stabbing, now shooting. What's next? What are your kids going to be like? What kind of community are you going to leave for your kids?"

The violence seemed to be escalating; another shooting—at Hassan's uncle—took place just days before Abdishakur's murder. And now it seemed that victims could be random.

"The Ahmednur situation—it was a wake-up call for everyone, to see that it could happen to everyone," says Abdirahman Mukhtar, a youth coordinator at Brian Coyle.

Somalis disagree about the cause of the violence. After experiencing bloody clan warfare during the Somali Civil War, the older generation is quick to point to tribalism. It's a topic that pops up frequently in online chat rooms, police point out. "Basically, the Madhiban guys killed two brothers and they lost the little kid that was killed a month ago," wrote someone with the screen name MJ-Pride on SomaliNet on the day that Nurki, the Coyle basketball coach and youth mentor, was murdered.

Others act offended at even the hint that the violence is clan-related. "There is no tribe which collects its youth to become a gang," says Shiekh Abdirahman Shiekh Omar, who serves as the imam of Abubakar As-saddique Islamic Center in south Minneapolis.

Young people and those who work with them say that to blame tribalism is as much a misunderstanding of Somali youth culture as assuming that all boys in baggy jeans are gang members. "Yes, Somalis have loyalty by tribe," says a 28-year-old youth worker. "But for anyone under the age of 35, tribe is not a big factor." In Somalia before the war, tribal leadership provided security, solved problems, and kept the peace. "If I go up to these kids and ask them, 'What has your tribe done for you?' they'll say, 'Nothing,'" says a 22-year-old youth worker.

Adds Fahia, who gives the Somali PowerPoint presentations: "The second generation, they have Somali names. But if you tell them they are Somali, they are more at ease identifying as Americans."

|

| Saeed Osman Fahia, the unofficial historian of Somalis in Minnesota, understands the social factors that have led to violence among Somali youth |

Some fear that the community's talk of tribalism could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. As more kids come to Minnesota from places where tribalism is a way of life, it could increase the gang's ranks, youth workers fear. Only about 150 of Minnesota's population of 60,000 Somalis are gang members, according to the Minneapolis police. But they are recruiting the next generation to the lifestyle. "The problem is the influence that is spreading," says the 28-year-old youth worker. Since the recent string of murders began last December, there have been at least as many shootings as killings. "Imagine if every shooting resulted in murder, how high that number could be," says Mukhtar.

Police say the best way for Somalis to stop the violence is to cooperate with authorities by coming forward as eyewitnesses. But communication between Somalis and the police has been fraught with misunderstanding. Jeanine Brudenell, Somali community liaison with the Minneapolis Police Department, remembers holding a community meeting after one killing and getting a cold response. "They basically said, 'The police need to do more. Only when you do more, then we'll help you,'" says Brudenell. "At a meeting one of the elders said, 'We want you to make all the gang members go away.' That's a tall order."

Police interviewed at least 100 people the day Mohamed Jama was slain. "We believe some people actually saw what happened," says Commander Stu Robinson of the Brooklyn Center Police Department. "The people who actually admitted they were there have recanted. So we're really back to square one."

Hearsay also muddies the picture for investigators. Mukhtar, the youth leader, explains it this way: "The way my community works—they talk," he says. "They jump to conclusions by just hearing about rumors."

That "telephone game" became more evident in the Mohamed Jama case, says Robinson. "We had a couple of names that surfaced right away," he says, but they turned out to be in custody or out of the state when Mohamed was killed. Still, accusations about these men persist, leaving Somalis frustrated that officers don't arrest them, and cops frustrated that they can't get more information.